Articles and News

Where Is The Luxury Jewelry Market Going, And Where Do You Fit In? | July 22, 2015 (1 comment)

Merrick, NY—Where is the luxury market going and what will it mean for makers and sellers of luxury jewelry? Recent articles on the subject—declining sales, disinterested Millennials, closing stores—alarmingly suggest it’s headed for big trouble.

Much is changing, and it’s not going back to what it used to be. But it’s not the first time that established luxury companies have had to adapt to dramatic change in order to survive, so it’s safe to say the luxury jewelry industry is not standing on the edge of a precipice with one foot off the cliff and the other on a banana peel.

Two of the world’s best-known luxury brands, Hermès and Louis Vuitton, both began by offering products for a lifestyle that went away. Hermès was a saddle maker, and Louis Vuitton got its start making custom steamer trunks. The advent of railroads, cars, and eventually airplanes would forever change the travel industry they served, and could have quickly rendered both companies irrelevant if they hadn’t adapted to the changing times and started viewing themselves as purveyors of luxury, not purveyors of saddles or trunks. Today, Hermès handbags and scarves remain the ultimate accessories in a crowded field, and the company just posted a 9.7% sales gain in Q2, on top of an 8% gain in Q1—and that despite the weak euro and a slowdown in Asia. Louis Vuitton, meanwhile, has parlayed its reputation for fine travel gear into a conglomeration of global brands representing the luxe life.

As for luxury jewelry, the future will require new ways of merchandising, new ways to reach the customer, and product that fits changing lifestyles and spending patterns, but there will be a future. In a multi-part series, The Centurion Newsletter will explore how that future is likely to look.

We begin by examining who is the luxury jewelry consumer.

Prior to 2008, democratization was the big trend in luxury. Whether it was creating a lower-priced diffusion line or introducing a few entry-priced products, the goal was to invite as many as possible to the party. When the recession hit, democracy went out the window as far as luxury was concerned. Marketers wrote off aspirational luxury consumers who were hit harder by the recession than their ultra-rich counterparts, and redoubled efforts to tempt those who made it through the recession unscathed with rare, exclusive products aimed only at the privileged few.

Luxury is back and bigger than ever. Bain & Co. estimates U.S. luxury spending rose 5% last year, to about $73 billion—a total greater than that of Japan, Italy, France, and China combined. And to paraphrase Mark Twain, reports of the aspirational consumer’s death are an exaggeration. According to data from The Shullman Research Center, this customer is alive and well and collectively driving more luxury purchases than the proverbial and elusive super-rich.

Shullman’s research shows that while 58% of very high income Americans (HHI over $250,000) made luxury purchases in the previous year but only 24% of the merely affluent (HHI $75,000-$249,999) did, the actual numbers are far more compelling. The very high-income segment accounts for about 3% of Americans, while the affluent segment accounts for 38% of all American adults. While the very high-income demographic spent the most on average for each luxury bought, and bought the most luxuries per adult, in real numbers that’s still about four million very high-income customers to 22 million affluent customers—not to mention that every brand and retailer is chasing those very high-income customers while the merely affluent are often overlooked. And that doesn’t even take into account the mass market (HHI <$75,000), which accounts for another 20 million consumers who may buy luxury rarely but still represent some untapped potential.

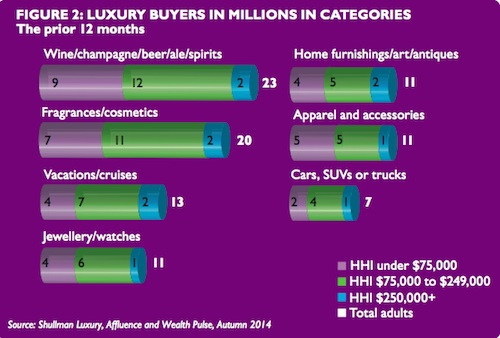

This chart from the Shullman Luxury, Affluence and Wealth Pulse shows there are 18 million more luxury buyers in the first tier of affluence (less than $250,000 HHI) than super-rich.

The fine jewelry industry has raised an alarm with valid cause for concern. While the high end has been doing well—evidenced by jewelers’ sales and solid results at high-end shows like Centurion, Couture, and Luxury—fine jewelry’s total share of the luxury market is eroding and sales are being lost to other luxury categories. Meanwhile jewelers, like everyone else, are trying to figure out what makes Millennials tick and, more importantly, buy.

Shullman’s Luxury, Affluence, and Wealth Pulse report from Q4 2014 asked respondents “What luxury products or services did you buy in the past 12 months?” From a list of seven categories provided, the top two categories, wine/champagne/beer/spirits, and cosmetics/fragrances are ones Shullman considers to be more affordable luxuries. Jewelry and watches came in fourth overall and second below vacations/cruises in terms of more costly luxuries. According to the survey, an estimated 11 million adults bought jewelry and watches in the previous 12 months; of those, 6 million fell into the “affluent” demographic, four million into the “mass market” demographic, and only one million in the ultra high-income demographic. Those consumers are a highly valuable segment of the luxury market, but the merely affluent—and even the mass market—constitute a substantial portion of the luxury space.

This chart from the Shullman study shows that when it comes to buying individual product categories, the super-rich may spend more individually, but the merely affluent wield a huge amount of clout collectively.

Is the best choice for a luxury jeweler to chase the elusive top tier that every other luxury marketer is chasing too? Or is casting a wider net going to be a better strategy?

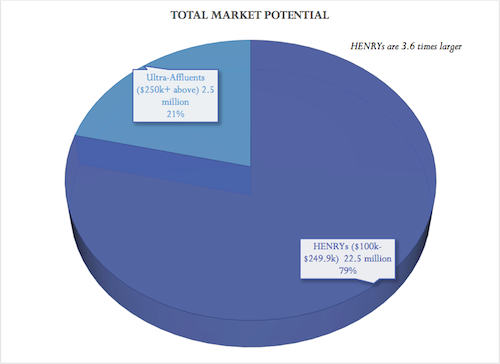

Pam Danziger, president of Stevens, PA-based Unity Marketing, comes down firmly on the side of the wider net. She believes the strength of the luxury market in the future lies in reaching that next tier of consumers, whom she has dubbed HENRY, an acronym for High Earner Not Rich Yet. These are the consumers earning $100,000 to $250,000 (slightly higher than Shullman’s $75,000 base), who can afford better-than-average goods but are not regular purchasers of the top tier. In the world of good, better, best, these are the customers for “better.”

$100,000 is the starting point for the top 20% of American consumers, who are the heavy lifters when it comes to spending. But the ultra-rich actually don’t spend that much as a percentage of the total economy, says Henry Blodget of Business Insider. Mainstream consumers drive most of the economy, but the HENRY group comprises nearly 90% of the affluent consumer market, with nine times as many as the ultra-rich. An ultra rich consumer may spend two and a half to three times more than a HENRY consumer, but collectively the HENRYs have a market potential three to four times greater than the ultra-rich.

Researcher Pamela Danziger says the high earner who is enjoying a degree of affluence but isn't rich yet (HENRY) offers tremendous potential for luxury sales. They may have less to spend per purchase than the ultra-rich but they're far less elusive. Chart: Unity Marketing

Retailers and brands that want to attract the HENRY customer have to blend strategies from both the high end and the mass market, says Danziger. She points to both Costco and Nordstrom as examples of retailers with a strong HENRY following.

From mass, it’s critical to emphasize value, as the HENRY customer is seeking a good return on investment and wants to be appreciated for being the savvy, educated (2/3 of HENRYs are college grads) shopper they are. In Costco, for example, the atmosphere may be no-frills but the merchandise is always well maintained and well organized and the employees are cheerful, friendly, and helpful.

From the high end, emphasize high quality, superior materials and workmanship, outstanding service, pride in ownership. Nordstrom successfully captures both an ultra-affluent and a HENRY customer by offering carefully selected and edited merchandise across a range of price points and, of course, its legendary reputation for customer service.

But income only tells part of the story. Psychographics are as important as demographics when targeting a luxury consumer. The Luxury Retail Landscape Report, published by Nielsen in May, concurs with Shullman and Danziger that luxury no longer is exclusive to the super-rich and that luxury retail has moved (or returned, as some might say) to the mainstream U.S. consumer.

The Nielsen report says 33% of all consumers are luxury-buying consumers and 41% aspire to be. 26% are non-luxury buying customers.

Of the 33% that are current luxury customers—your customers and potential customers—Nielsen breaks out five market segments. These are: New Luxury, Established Luxury, Keeping Up With The Joneses, Younger Aspirationals, and Older Aspirationals.

New Luxury consumers, ages 25-44, value image, status and quality. They’re typically urbanites, they strive to achieve a high social status and like to broadcast a lifestyle that impresses others. They are willing to pay more for high quality products, but being highly connected, they also seek ways like social media to talk about and engage in the hype around new products. They shop at places like Anthropologie, Bloomingdale’s, and Crate & Barrel. They spent at least $500 last year on clothing (including athletic shoes) and cosmetics. They live in places like San Jose and San Francisco, CA, Washington, DC, New York, Boston, or Seattle.

The Established Luxury customer is probably most familiar to luxury jewelers. Age 45+, they’re typically wealthy suburban homeowners willing to pay more for high quality products. They prefer timeless classics and subtle status cues to flash and trends, and typically spent more than $500 last year on clothing, fine jewelry, sports equipment, and cosmetics/perfume. They shop at stores like Neiman Marcus, Brooks Brothers, Pottery Barn and live in places like Martha’s Vineyard, MA, Jackson, WY, and Bridgeport-Stamfort, CT.

The notion of keeping up with the proverbial Joneses is not dead. This luxury customer values image and status, and likes to live a lifestyle and wear brands to impress others. Quality matters less than image. Typically under age 55, this customer tends to be an upscale suburban family that shops at Banana Republic, Macy’s, Crate & Barrel, and has spent more than $500 last year on clothing, cosmetics, shoes, and kids’ clothing. You’ll find lots of them in Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, or Las Vegas, and they respond to messages that position your products as symbols of success, affluence, and belonging.

Younger Aspirationals are under age 55, and are midscale suburban families that don’t typically buy a lot of luxury, though they’d like to. Luxury should feel like an indulgence and a reward to this customer. They’re willing to pay more for products consistent with the image they want to project, they’ll wear designer brands to impress others, and follow trends. Their spending is focused more on kids’ clothing and they shop at more budget-friendly stores like Burlington Coat Factory, Express, and Old Navy. Look for many of these consumers in or near college towns.

Older Aspirationals value luxury but don’t typically buy it. This customer tends to be rural, over 55, and price-conscious. To them, brand name is the best indication of quality, but they spent less than $500 last year on clothing, shoes, and sports equipment. Like the younger aspirational consumer, luxury feels like an indulgence or reward. They’re likely to shop at discount stores like Stein Mart or midrange stores like Chico’s, and they live in communities like Ocala, FL, Johnstown, PA or Pittsfield, MA.

This table from Nielsen shows 10 top populatino centers with a concentration of each of the five segments of existing luxury customers live. Source: Nielsen Luxury Retail Landscape Report.

“As U.S. consumers continue to recover from the Great Recession and feel more confident opening their wallets, luxury retail spending will likely continue to grow. This includes consumers who may not have had access to luxury brands in the past, as luxury goes more mainstream. And as more and more households become multi-generational, building loyalty among families presents great opportunity. Brands that invoke heritage like Brooks Brothers can capitalize on the history and meaning behind of the brands across families and generations. Continued growth of the luxury market requires diligence in understanding the evolving tastes of consumers entering the market and the distinct values these consumers place on the luxury items they purchase,” says Nielsen.

Top image: aliexpress.com