Articles and News

New Moissanite Trips Up Jewelers With Older Testers; GIA Releases Guide To Spotting Synthetics | July 27, 2016 (0 comments)

Merrick, NY—With the diamond industry in turmoil over both synthetics and wavering consumer demand, few jewelers remember worrying about the implications of synthetic moissanite and switched stones when it first hit the market 20 years ago. But as one better jeweler discovered, technology waits for no one, and improvements in moissanite quality and color means the old testers retailers relied on are of no use to identify the new material.

For years, cubic zirconia was the leading diamond simulant. But it’s easy to detect at the counter using a simple thermal conductivity test with a hand-held device.

Then synthetic moissanite was developed, with a hardness of 9.5 to diamond’s 10 and some optical properties that surpass diamond. And because its thermal conductivity is similar to diamond, the traditional test used to distinguish CZ was useless for moissanite. 20 years ago, it caused some intense, but thankfully short-lived, anguish among jewelers.

Moissanite has been fairly easy for trained gemologists to distinguish, as it has a double-refraction property different from diamond. It also typically had a color comparable to a J-K-L diamond, with a slightly greenish tint. An experienced gemologist could spot it by eye, but less experienced sales associates had no means of easily testing at the counter, explains Danny Kessler, co-CEO of Dallas-based Sy Kessler, a supplier of gem instruments.

But moissanite is electrically conductive, whereas diamond isn’t. (A few diamonds are, but it’s very, very rare.) Sy Kessler developed a handheld diamond tester that measured electrical conductivity as well as thermal conductivity, and once again, jewelers had a quick and easy solution and life was good.

But last year, Charles & Colvard, a leading producer of synthetic moissanite, introduced Forever One, a new and improved formula with D-E-F color and much less electrical conductivity—in fact, barely any, says Kessler. The company also offers Forever Brilliant, which has G-H color, and its J-K color now is being marketed as Forever Classic. The Forever One product comes in round, cushion, Asscher, oval, and square cuts.

“The old [tester] technology doesn’t work,” Kessler told The Centurion bluntly. “Forever One has such slight conductivity that if you touch it to any tester, it will say diamond.” And by then, the industry had a much bigger concern: synthetic diamonds slipping into the pipeline undetected. Any worries about moissanite were relics of the good old days—or so jewelers thought.

Time to build a better moisstrap. Sy Kessler developed the Gemoro Pro M-3, a standalone moissanite tester, as well as the GemOro Testerossa combination diamond, moissanite, and white sapphire tester, in conjunction with Charles & Colvard, says Kessler. It measures a much more minute level of electrical conductivity for the new stones. The Charles & Colvard website has a page dedicated to the testers, urging jewelers to be sure they use two with every sale: both the new Gemoro moissanite tester and a diamond tester.

“They want to be good citizens, not to set jewelers up for fraud. They’re not going to release a product without a solution,” says Kessler. “The problem is that few jewelers know they need it.”

The Forever One product hasn’t been on the market that long—it was introduced less than a year ago—but already it’s creating controversy. The most famous, of course, are consumers who accused Kay Jewelers of switching their stones, but recently a better independent store inadvertently got burned as well.

Like many independent jewelers, Gerald Amerosi of Gerald Peters in Staten Island, NY, will buy diamonds off the street from consumers. A longtime trusted customer came in to sell a diamond, and a quick swipe of the handheld tester he'd had for years didn’t show it wasn’t diamond. But when Amerosi sent the stone to GIA, as he does with all diamonds he gets off the street, it proved to be a Forever One moissanite.

“Existing devices aren’t going to find [the new moissanite]. As far as we knew, the testers were 100% accurate, but you have to read the fine print, which says they’re not 100%, and recommend a secondary check.”

Kessler says consumers are famous for not reading instructions—and jewelers are consumers.

“Electrical conductivity is so faint in the new material. The new tester is hypersensitive, but unfortunately body oil also is electrically conductive, and if you get some on the stone, it will even say that a diamond is moissanite. You have to read the instructions, which say to wipe the stone carefully with a Selvyt or other cloth.” Kessler also reiterates the need for a secondary check, because he says even experienced jewelers who could visually see the difference between [original] moissanite and diamond will have a much harder time with fancy cuts and with the new material.

Amerosi blames himself for not taking the time to do a secondary check. “We’re all busy, but you can’t do this fast. You have to use a loupe, you have to be educated by GIA, and you have to check for double refraction. You can’t take shortcuts. You have to slow down. You can’t rely on the handheld.” The customer believed the piece to be diamond and Amerosi had no reason to suspect otherwise, but he admits it was an expensive mistake. He still has the stone and is willing to send it to a third party to check again.

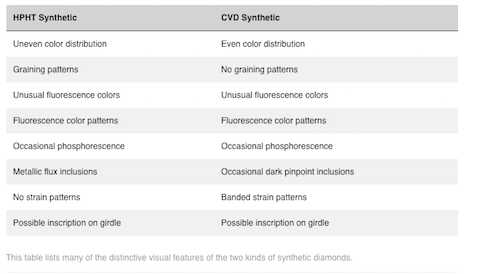

Separately, GIA’s distinguished research fellow Dr. James Shigley has just published a new article about identifying lab-grown (synthetic) diamonds. This comprehensive article explains how they’re made, what kinds are available, and how to identify them. He cautions that even though trained gemologists may not be able to recognize synthetic diamonds, GIA is able to identify them in the lab. Click here to read Shigley’s article in full.

The chart above lists distinguishing visual characteristics of both HPHT and CVD synthetic diamonds. This is one of many visual aids in Dr. James Shigley's article about synthetic diamond identification. Photo: GIA