Articles and News

15 Month Countdown: Retailers Get Ready For Chip Credit Card Switch In 2015 | July 09, 2014 (0 comments)

Merrick, NY—Change is coming to the way Americans use credit cards, and retailers who aren’t ready when the switch occurs will be left holding the bag for fraudulent purchases.

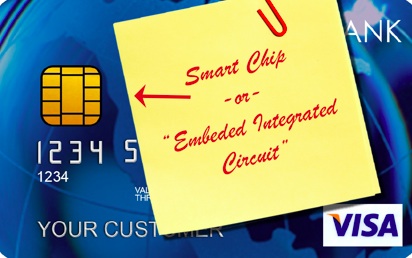

The United States is the last major market in the world that uses credit cards with a magnetic strip on the back. All other major markets long ago migrated to cards with chip and PIN (personal identification number) technology, called EMV, an acronym for Europay, MasterCard, and Visa, the three companies that originally developed the technology. EMV (example at left), the standard for most of the rest of the world, is far less vulnerable to fraud than the magnetic strip system. As a result, criminals—always searching for the path of least resistance—turned to the United States, resulting in a sharp increase in fraudulent transactions here. EMV technology has reportedly cut fraud on individual cards as much as 80% in markets that use it.

There still is debate as to how much EMV can protect against massive data breaches such as the ones Target and Neiman Marcus experienced last Christmas. Those came from hackers breaking directly into either the retailer’s computer system or that of a third-party vendor; at present most experts believe EMV may cut down on the severity of such breaches but won’t entirely eliminate the threat. Instead, it needs to be part of a multi-pronged approach to fraud prevention.

“Today’s advanced technology broadens the threat landscape for merchants and offers multiple ways for cyber criminals to steal cardholder data (while in motion or at rest) and then use the stolen data to produce counterfeit cards,” explains Cynthia Kurczewski, spokesperson for First Data, a global payment solutions company.

“It is critical to protect against all of these threats. To prevent the large-scale data breaches that we’ve seen recently, merchants should implement a multi-layered approach to payment security. Focusing on only one or two of these problems can still leave the merchant vulnerable to having card data stolen and misused.

“While EMV protects against card counterfeiting and lost and stolen cards, merchants should also consider data protection solutions that include encryption, which protects card data in motion, and tokenization, which protects card data at rest.”

The chip will be embedded on the front of each credit card. To make the technology effective, retailers will have to have payment terminals that are capable of reading the information embedded on the chip. Image: goedps.com

Currently, credit cards issued in the United States typically have only a magnetic strip on the reverse to store customer information. (Image: jack-wolfskin.ch)

According to an article in the Wall Street Journal, the reason it’s taken the U.S. credit card industry so long to switch over is both cost and technology. Technology-wise, one appeal of the chip system is its ability to work offline, independent of contact with the user’s bank. But in the United States, Internet connectivity is generally reliable enough that it wasn’t a driving factor. Plus, the Durbin Amendment passed as part of the Dodd-Frank legislation in 2010 requires debit transactions to go across two networks, so that took some time to sort out.

But the real holdback is cost. Collectively speaking, switching over will cost card issuers approximately $3 billion, and merchants approximately $2 billion, according to data from T-SYS, a Columbus, GA-based payment solution provider. And BankTech.com estimates the upgrade cost per device will range from $200 to $5,000.

Until recently, the cost-benefit analysis of migrating to EMV simply didn’t warrant the expense, because other countries had far more fraud problems than we did. In short, it was cheaper for banks and credit card companies to make restitution to businesses for fraudulent purchases on stolen or swiped cards than to invest in preventing them.

No more. As other markets switched to the chip-and-PIN system, the criminals came here looking for an easier target (no pun intended). By last year, half of the credit card fraud in the world was happening in the United States, despite the fact that only 25% of the transactions occur here.

The credit card industry now has set October 2015 as a key date for the change to chip-and-PIN technology. More specifically, it’s the key date for a shift in who’s going to be liable when fraud occurs. By that time, credit card issuers in the United States will have replaced cardholders’ current cards with new cards that have the microchip. Merchants still can use their old swipe terminals after that date if they wish—but if fraud occurs, they’ll be on the hook for the money themselves.

“Whichever party has the lesser technology will bear the responsibility,” said Carolyn Belfany of MasterCard in the WSJ article.

What it means is that if the merchant is still using the old swipe system, and the criminal has a chip card, then the merchant will be out the cost of whatever was fraudulently purchased. But if the merchant has the new system and the bank hasn’t yet issued a new chip card, the bank will be liable for the fraudulent amount, not the merchant. Gasoline stations have until 2017 to upgrade auto-pay pumps.

But the key point is not to just shift the liability, Belfany told the Journal. It’s to ensure that card issuers and merchants invest in the migration together. “This way, we’re not shifting fraud around within the system; we’re driving fraud out of the system.”

The change does put some burden and expense on business, because every payment application, point-of-sale solution, payment terminal, and processor network must be replaced or updated to work with the new system. Still, for a high-end retailer like a jeweler, the cost of installing the safeguards has to be weighed against the cost of essentially giving away a diamond or a Rolex if it was fraudulently purchased in a transaction that could have been prevented with the new equipment.

An independent retailer will need to have either a terminal with an integrated EMV reader, or attach a peripheral EMV device to their existing terminal, First Data told The Centurion. Retailers would procure this equipment from their acquirer/processor and the associated cost, if there is one, is at the discretion of the acquirer/processor.

There are several options, however, that could help keep costs down: First Data’s Kurczewski says adding a peripheral EMV device to an existing terminal would be the most cost-effective option. Her firm anticipates that approximately half of its currently active merchants will be able to use that option.

EMV technology will not affect payment methods for e-commerce, catalog, and other “card not present” transactions. But future technology is being developed that will allow more secure mobile (m-commerce) transactions.

Here’s why EMV is better at preventing fraud: with magnetic strip cards, a cashier could surreptitiously swipe the card through a card-copying machine and capture the cardholder’s information before putting the sale through the store’s payment terminal. Or hackers could alter point-of-sale devices with card readers to capture cardholders’ info, as has been done on ATMs and gasoline pumps. But with the chip and PIN system, the information embedded in the chip is useless without the accompanying PIN number. For now, says the WSJ article, most transactions still will be done by signature but the technology is in place to switch to a PIN at any time.

Top image: Creditcards.com