Articles and News

Daymond John, Entrepreneur And ‘Shark Tank’ Investor, Tells Jewelers Failure Isn’t An Option | April 05, 2017 (0 comments)

Scottsdale, AZ—Daymond John, entrepreneur, author, and founder of FUBU apparel, regaled Centurion attendees with both funny and insightful examples of how he grew from a poor kid in Queens, NY, to one of the most successful entrepreneurs in the apparel industry and a regular investor on TV’s Shark Tank. Read how his book, The Power Of Broke, inspired Centurion president Howard Hauben here.

John’s first entrepreneurial venture was in first grade. He’d scrape the paint off pencils, then paint the names pretty girls on them and sell them to the boys to give girls they liked (instead of the more common first-grade form of endearment, knocking their teeth out, he said.)

“Then I realized the girls would pay twice as much for my pencils, so I sold directly to them till the principal shut me down,” he laughed.

“My father left when I was 10, and my mother had to work three jobs just to keep the roof over us.” John got a job for $2.25 per hour to hand out flyers announcing the building of the Coliseum Mall. He put the money in the cookie jar and his mother patted his head and told him, “You understand something the entire world doesn’t understand. Responsibility is something that must be taken, it can’t be given.”

“We didn’t know anybody with money,” he said. “On TV we never saw anyone that looked like me that had money. The only entrepreneur I saw on TV was Fred G. Sanford, and it doesn’t look like he did well.”

Hip-hop music, with its roots in the Bronx, was just beginning when John was growing up. It was the disruptive technology of the day. “It was our version of Twitter, and kids were communicating through music about everything they love, hate, wear, etc. It’s not something you listened to, it’s how you lived, and it came with a way to walk, talk, and dress. We would go out into the park and take the power cords out of the street lights and plug into record players and dance all night.”

John says the real heroes of his neighborhood were the ones getting up at 5 a.m., getting their kids ready for school and then going to work and trying to further themselves, but the kids “never saw the heroes. We saw drug dealers driving by in fancy cars,” he said.

Meanwhile, an entrepreneur named Russell Simmons had begun recording the music, launching a hugely successful record company called Def Jam. It expanded hip-hop from inner-city phenomenon to a global musical genre, and launched the careers of many renowned artists such as LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys, and so on. (Editor’s note: Russell Simmons, also a renowned global philanthropist, was a co-founder of the Diamond Empowerment Fund.)

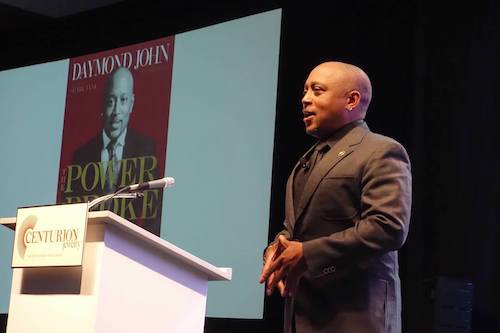

Apparel magnate, author, and Shark Tank investor Daymond John speaks to jewelers.

A turning point for Daymond John was when he was working at the Coliseum Mall (the same mall he’d once handed out flyers to announce its construction). He noticed that the entrepreneurs were the ones coming first in the morning and leaving last at night and pulling people in the neighborhood up with them.

“I always thought bosses and small business owners were supposed to be mean, nasty people like J.R. Ewing or something. But I would go to them and ask for wholesale on things to get onto rappers—and I got things on consignment.”

John had been at the concerts of some legendary musicians: David Bowie, the Commodores, and many more, but, “I had never seen someone who looked like me and walked like me till the Run DMC concert.”

That was in 1984 in Philadelphia. 30,000 people at the Spectrum were dressed in a uniform of hip-hop: Adidas sneakers and Kangol hats.

“Who sent out the memo? There wasn’t Twitter or Internet at that time! There weren’t cell phones at that time!” he said.

“My life turned around. I set goals. Every night I set goals. Some expired in six months, some in five years, some in 10, and every six months I re-set the ones that expired. My mother said to take inventory of yourself. Your assets are what feeds you, your liabilities are what eats you.”

John got another job because he wasn’t getting enough hours at the mall. “I got a job at Red Lobster right when they introduced cheddar bay biscuits.” Joking that the biscuits were a turning point for the restaurant, he grew serious again. Hip-hop culture might have a look, but mainstream brands wanted no part of it.

“If Donna Karan doesn’t like inner city kids and Ralph Lauren doesn’t like black people and Tommy [Hilfiger] doesn’t like rappers and Timberland said, ‘we don’t make our boots for drug dealers,’ I want to create a uniform for this market! If you make the best boot in the world, how often do people buy them? But if I’m buying a new pair every month and you call me a drug dealer when I’m working at Red Lobster, I’m not going to buy them anymore! I’m going to make boots that everyone can afford!”

He went home and came up with the acronym BUFU, for By Us, For US. “I didn’t do my homework. At that time in my neighborhood BUFU meant something entirely different,” he laughed. He went home and changed it to FUBU.

“I bought a hat and my mother said, ‘I can teach you how to make them.’ It was 1989, 30 degrees, I’m standing shivering outside the Coliseum Mall selling hats. For two years, I took 10 shirts and went to every video site I could. I got kicked out of many, but the ones I didn’t I put [the shirts] on rappers. Dr. Dre, Will Smith, et cetera, and people started to see them in a video and they’d want to wear them. I went around to small stores and painted the FUBU logo on security gates. It was free—but it would have cost zillions if it were on billboards.

John approached rap star LL Cool J, who still lived in the neighborhood. “I didn’t know him well but I knocked on his door. Could he do us a favor and hook us up with a superstar like Milli Vanilli?”

Unfazed that the young entrepreneurs preferred Vanilli’s music over his own, LL told them to go to the record company offices and wait in the men’s room with samples. “That’s the one thing they can’t have their secretaries do for them,” he told John. John’s partner, meanwhile, was a little more sensible. He suggested the two simply stalk LL himself. They went back to LL’s house and asked him to take a picture with their shirt on. “He said, ‘I am going to LA and getting paid millions to wear Nike, Timberland, etc., and I am face of your shirts? And you only have 10 and they stink!”

Perhaps it was payback for the Vanilli request, but Daymond John said insulting his business was kind of like insulting his daughter. Luckily, he was wise enough to bite his tongue, not criticize what LL was wearing at that moment, and ask, “what’s wrong with my clothes?” It turned out that LL didn’t like the purple box on the shirt. It was an easy fix, and after getting a photo of the longest-running platinum rapper wearing FUBU, the rest, as they say, is history.

Almost.

John took his samples and headed to the MAGIC apparel tradeshow in Las Vegas. He had made 300 flyers with the photo of LL and a handwritten ad saying, “FUBU had signed a million-dollar deal with LL Cool J, kids have seen the shirts, and want the shirts and we will be at MAGIC.” But he didn’t have money to get a booth or even badges. "We set up in a room at the Mirage and snuck in and told buyers, ‘Psst! We have FUBU in our hotel!’” He got $300,000 in orders—with absolutely no idea how he was going to get the items produced.

“27 banks turned me down. I told my mother; she didn’t know 27 banks existed! She tapped the equity in the house and got a $100,000 loan. I have no idea how because the house was worth $75,000. We emptied out the house, filled it with industrial sewing machines, got seamstresses, and made the clothes. “We were selling clothes and cranking and doing well and suddenly we were about to lose the house. We were being choked by the float.”

But this was the moment that he realized failure simply was not an option. John's mother said, “you need other people’s money, a strategic partner.” John went back to waiting tables at Red Lobster and got his mom $2000, which she used to take a newspaper ad: “One million dollars in orders—need financing!”

30 people saw the ad and called, said John. A lot had names like "Nails," he joked, but three were real, one of which was the textile division of Samsung. “The deal they made was that I had to sell $5 million in clothes in three years or they would keep the brand. I was about to lose the house so I had no choice. Failure wasn't an option. But I knew I wasn’t going to sell $5 million in three years, because I knew my customers: we sold $30 million in three months!”

In 1999, John’s now good friend LL Cool J was tapped to star in a Gap commercial. The retailer asked the rapper to write his own lyrics about the brand’s easy-fit jeans. He did—and inserted “For Us By Us on the low” into the lyrics. He performed the rap for the commercial wearing Gap jeans and shirt and a FUBU hat, rocketing the company to more than $350 million in sales. He even slipped a plug for the brand into his rap: "for us by us on the low."

Ultimately, however, it’s still about doing what you love. Much of what’s been created lately is just another way to deliver, said John. “Uber is still a limo service and a Snuggie is a blanket with holes in it. My speech is about reminding you what got you here and what you love doing.”