Articles and News

HOW TO MAKE NEW PROFITS FROM OLD WATCHES | July 11, 2012 (0 comments)

Merrick, NY—Despite the proliferation of cash-for-gold shops, luxury jewelers, along with other purveyors of luxury goods, often find themselves having to walk a fine line between selling lasting value and managing customer expectations of what that value means on the resale market. While the materials, workmanship, or both can justify an item’s costliness, it’s a rare item that will gain enough value to fund college tuition. Most luxury goods are bought at retail but sold back at wholesale (or less.)

While it’s disappointing news to a consumer hoping to make some quick cash, for a jeweler, resale can be a profit center because there are always customers for second-hand luxury. It’s as true for cars, home furnishings, apparel, and, of course, jewelry.

It’s especially true of expensive watches, says consumer watch blogger Ariel Adams. In this article in Forbes, Adams says buy a luxury watch because you love it, not for investment. Unless it’s a Rolex or a Patek Philippe, chances are it’s not going to net even what you paid for it if you try to sell it.

But even with Rolex and Patek, which Adams says are most likely to hold their value, he puts the emphasis on “hold” their value. According to his Forbes piece, Adams says your grandchildren are more likely than you are to benefit from any increase in the watches’ value. He cautions that the majority of other watch brands lose a lot of value right after purchase, and some brands that were especially hot before the recession have not fared so well since.

“People lose confidence in the prices and that makes those brands risky from a value perspective,” he told The Centurion. Whereas gold and diamonds have fluctuating prices set by the market, desirability and exclusivity are what drive watch prices.

Edward Faber of Aaron Faber Gallery in New York, NY, is a renowned expert in vintage watches. He agrees Rolex and Patek are the best-selling brands in the vintage market, but says it doesn’t take generations to see the value multiply. For example, he says, the Patek 3445 that debuted in 1962 (one is shown above left) was the brand’s first auto-date, and it sold for $800. In 1990—roughly one generation’s worth of time—it was fetching between $4,500 and $5,000 on the vintage market. But by 2000, only 10 years later, its value had doubled to $10,000.

Faber bought a used Rolex Daytona (the brand’s iconic chrono) in steel, in 1979. He paid $300. Now, he told The Centurion, vintage ones sell for $22,000-$25,000.

Vintage Rolex Daytona watches like this one can fetch upwards of $22,000.

“Flipping [watches] doesn’t exist. But selective models with guaranteed provenance gain value, sometimes appreciably so in [as little as] three to five years,” he says.

Two more notable watches: Left, a Patek Philippe in rose gold, and right, a Rolex pink President. Photos courtesy Aaron Faber.

Interestingly, with the current economic crisis in Europe, he’s seeing wealthy foreign customers who are nervous about currency valuations looking for small, portable places to put their money—and that includes valuable vintage watches and fancy-color diamonds. And, because watch manufacturers have the chutzpah, as Faber puts it, to keep increasing value (i.e. price) regardless of economy, yes, selectively purchased models can be a good hedge. But he emphasizes selective models. Just because it’s a good luxury watch doesn’t mean it’s a good resale bet.

“I had a European client just tell me he was offered a great deal on an Audemars Piguet: 30% off. Great, I said, you’ll only lose one-third of what you paid [if you sell it].”

Still, Audemars Piguet is one of the brands Faber says usually catch a collector’s eye, along with A. Lange & Söhne, Vacheron Constantin, and F.P. Journe. The emphasis on these brands is very fine quality and limited production, but the price must be appropriately discounted [for resale], he says. Adams says IWC and Omega also have resale potential, but Faber says while they’re excellent horological timepieces, their trading value in the market is about 25% to 35% of the retail price.

Still, that gives jewelers great profit potential, because even selling at half the price of a new model gives the jeweler 100% profit on a watch he picked up at 25% of retail. And the jeweler gets the cachet of selling top brands without the high financial commitment asked by brands for dealers to stock new models.

Audemars Piguet is a brand with cachet for collectors. This is its Quantieme chrono. Photo: Aaron Faber Gallery.

“Lots of people don’t want to spend top dollar [for luxury watch brands],” Adams told The Centurion. They’re perfectly willing to pick up a coveted name second-hand because they’re planning to wear it, not sell it.

Adams thinks smaller retailers can have a tough time finding enough good pre-owned stock, but Faber disagrees. “There’s a huge secondary market!” he says emphatically. Aside from what’s online, there’s a market event once a month in the USA, he says. He recommends jewelers join the International Watch and Jewelry Guild (IWJG) to gain access to product and market events.

Time does need to be invested to learn what will sell and for how much, but the basics are simple. Faber says these five things (in descending order) matter most in vintage watches:

- Brand. Rolex and Patek Philippe, in particular. Adams says Omega and IWC are good bets too.

- Presentation and condition. Does the watch have its original box and papers? That counts for a lot, says Faber. So does the condition of the watch itself—obviously, the less beat up it is, the better—but not necessarily restored!

- Metal. In descending order, platinum, rose gold, white gold, yellow gold, and stainless steel are most desirable. But here’s a caveat: sometime steel can trump all others in value, if it’s a rare vintage model made in steel when newer ones were made in gold.

- Complications.

- Rarity.

Faber recommends the Specht Sheet (by Ken Specht) as a valuable guide to vintage watch value and pricing, and cautions that the definition of “vintage” is very specific. Vintage watches generally fall in a 50-year span dating from 1935 to about 1985. Anything prior to 1935 is antique, not shockproof and generally lacking complications. After 1985, he says, so many models were created in CAD that they really can’t be considered vintage.

But don’t ignore watches of more recent years, suggests Faber. Going back to what Adams says about some customers not wanting to pay top dollar for a coveted brand, Faber adds that trade-in is a huge opportunity for jewelers to both acquire second-hand stock and sell costlier new watches.

Trends To Watch. “I’ve never seen so much passion and debate as there is around size,” says Adams. “I’m surprised at the emotion [it drives].”

Indeed, if there’s one thing most watch lovers can agree on, it’s that bigger is better. Women, especially, have made a jump in size, now preferring cases between 36mm and 40mm, much larger than a traditional “ladies’” watch. Adams credits fashion designer Michael Kors with driving this trend.

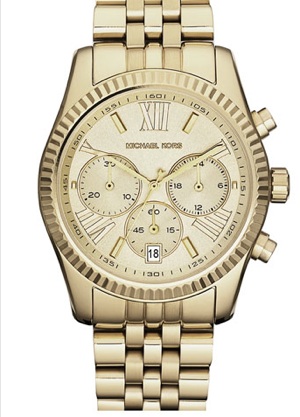

“It’s not a luxury watch by any means, but it’s a great gateway watch,” says Adams of the Kors line, which is typically priced under $500 and sold in department stores.

Fashion designer Michael Kors' tremendously successful watch line has helped to drive both a trend to bigger watches and enthusiasm among women to become watch collectors. This "Lexington" model retails for $250.

But because women’s watches have grown larger, that’s accelerated the trend for even bigger men’s watches, says Adams. Men don’t want to wear a watch that’s the same size (or smaller!) than a woman’s watch. Now, says Adams, about 95% of men choose cases between 40mm and 44mm. But some men want to go even bigger, up to almost 50 mm.

The tremendously popular Michael Kors watches are helping to drive women’s interest in luxury watches, says Adams. He’s seeing more women becoming collectors, starting to exhibit interest in the exotic complications and the mechanics of fine watches. But still, he says, for a woman it’s still first and foremost about the look of the watch.

A new trend Faber is seeing is a growing interest in mechanical watches among affluent younger buyers, age 25-35. This generation’s whole life is digital, he says, but they’re suddenly growing fascinated with the gadgetry of mechanical watches. “They like feeling like they can get involved with time and interact with it, rather than just read it,” explains Faber.