Articles and News

LUXURY JEWELERS AT MOST RISK FROM FRAUDULENT SYNTHETIC DIAMONDS | May 23, 2012 (0 comments)

Antwerp, Belgium—Last week's discovery of a large batch of undisclosed synthetic diamonds in a parcel sold as natural has the industry on edge, but is especially worrisome for luxury jewelers because the stones in question, though small, were high quality. Disclosure of man-made stones, diamond or otherwise, is required by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission.

The International Gemological Institute (IGI), which found the stones, immediately issued a trade alert to other grading labs around the world, raising fears that significant numbers of these stones—purchased in New York—may already be in the market posing as natural. It's the diamond industry's worst nightmare coming true.

Initially, about 145 stones submitted to the IGI grading lab in Antwerp by a dealer who’d purchased a parcel of 1,000 were found to be synthetics created by the CVD (carbon vapor deposit) method. Following the initial discovery, it was determined that more than 600 stones in the parcel—which was sold as natural—were synthetic. At the same time, two separate parties submitted a smaller parcel of 10 synthetic stones to IGI’s Mumbai lab. IGI identified similar characteristics and believes all the stones are from the same source.

Are these isolated incidents, or the tip of an iceberg? Will jewelers or dealers now have to submit every single stone, no matter how small, for certification? If that must become the norm for every stone, what will happen to prices?

“Most better quality stones above 0.25 carat do go through the labs anyway,” says Russell Shor, senior industry analyst for GIA. But it’s because of the growth of online trading, not because of synthetics, he told The Centurion. “The Internet has driven the certificate revolution.”

Basically, says Shor, stones smaller than a quarter-carat can be problematic. And yes, if there’s a constant threat of synthetics leaking into the market, it’s going to drive prices up for better-quality stones if every stone has to be certified, or down, if it isn’t. It will affect the cost of any setting with small accent stones: for bridal jewelry, the part that delivers the most margins.

“Prices fall to the level of doubt,” Shor says. So without certificates to prove they’re natural, small stones can fall to the price of a synthetic even if they aren’t.

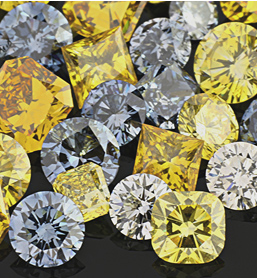

Both white and fancy yellow diamonds might be synthetic.

When the amethyst market was flooded with synthetics in the last decade, it drove prices down and created about a 50/50 chance that any given stone could be man-made instead of natural, but given the low price of even natural amethyst, there’s no cost-effective way to tell synthetic from natural. Hence, it’s both easier and cheaper to simply alert consumers that any piece of amethyst jewelry may contain man-made stones.

But amethysts aren’t diamonds. And while no consumer wants to be ripped off, luxury jewelers have the most to worry about. It may be more cost-effective for mass-market retailers not to get certs on small stones, simply taking the amethyst approach and alerting customers that synthetics are possible. Peter Yantzer of AGS Labs believes this eventually will happen. “It’s just too time-consuming to grade every five-pointer,” he told The Centurion.

But a high-end customer paying five figures may not want their natural stone surrounded by synthetics, even ones they know about. Batch testing parcels of smalls can lower the chance of synthetics sneaking into the pipeline, but the only way to be 100% certain every stone is natural is to test it. Yantzer says testing melee eventually could become a point of differentiation for a luxury retailer.

IGI isn’t the first lab to come across sneaky stones. The Diamond Trading Company Research Centre also recently alerted DTC sightholders to three separate submissions of synthetic stones for grading, to labs in India, China, and Belgium. Again, the stones bore similar characteristics, suggesting a common origin.

Though De Beers is involved in synthetic diamonds itself through its Element Six subsidiary, the DTC has warned that the presence of undisclosed synthetics in the market could cause irreparable damage to the integrity of the diamond supply chain and undermine consumer confidence in diamonds. (De Beers’ involvement in synthetics is so far limited to industrial applications.)

The DTC has a point—the conflict diamond issue taught the industry that “I didn’t know” isn’t an acceptable answer for either consumers or reporters. And the industry already fears the price differential between synthetic and mined stones—50% or more—can be a powerful motivator for consumers, even luxury consumers who simply want a stone that looks good and don’t want to pay top dollar for it. The huge emerging Millennial generation also may be a ready market for synthetics, as they’re both fascinated by technology and generally unwilling to pay full price for anything.

The good news is that CVD synthetic stones are fairly easily identified, and the lab caught the stones. The bad news is that it requires sophisticated equipment that diamond dealers—and retail jewelers—don’t yet have. HPHT-grown synthetics have telltale inclusions and growth patterns that a retail gemologist can see, but standard gemological microscopes are not sufficient to identify a CVD diamond as man-made.

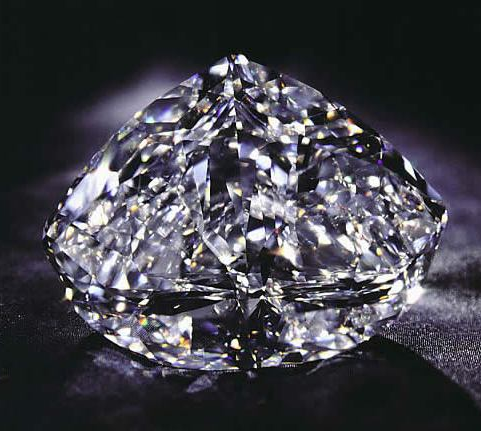

The stones found by IGI were mostly between 0.30 and 0.70 ct., F to J color, VVS to VS clarity, and with very good polish and symmetry. All were Type IIa, which is characteristic of synthetics, but Margaret DeYoung, a diamond industry consultant, says it’s also a characteristic of many very fine natural stones, such as the famed Golconda. And when such stones come up at auction, Type IIa is a strong selling point.

“They’re the purest, so when they’re white, they’re very white,” she told The Centurion. But they’re also often brown, and are the best candidates for HPHT treatment, she added.

Type IIa stones, such as the famous De Beers Centenary, above, are very pure and very white. All synthetics are type IIa, though many fine natural stones are as well.

Typically, CVD stones are spotlessly clean, says Yantzer, but the stones submitted to IGI contained inclusions such as feathers, pinpoints, or small dark crystals, which are very similar to natural inclusions. Chaim Even-Zohar of Tacy Ltd., which publishes Diamond Intelligence Briefs, is one expert who believes those stones were deliberately included during production. Not, he says, to make them more beautiful, but to make them appear more natural.

The problem isn’t synthetics, says AGS' Yantzer, it’s when they’re misrepresented and sold as naturals with the price premium of naturals. At GIA, the lab has encountered a number of undisclosed synthetic diamonds in the past few years, says Shor. In most cases, it simply issued a synthetic diamond report, but when it appeared the client was attempting to deceive the lab (such as resubmitting the same stone, recut), GIA turned their names over to the diamond bourses for appropriate action.

While early leaders in the synthetic diamond trade, such as Florida-based Gemesis, the former Boston-based Apollo, and Denver-based Lucent, pledged full disclosure, the industry has long feared that a less conscientious company would leak undisclosed synthetics into the market. Even though the growing process still has glitches and synthetics account for a very small percentage of the market, the dealer who brought the parcel to IGI had selected it from a much larger pile--suggesting they’re on the verge of becoming far more common as technology advances, and that there may be more fraudulent stones already in the market. Panic may be premature, but healthy concern is warranted.

For now, retailers’ best defense is to buy only from sources they trust completely, say both Shor and Yantzer. And hope that those sources aren’t tempted by a sweetly-priced parcel of smalls without a certificate.

“Right now, there’s no easy answer,” Shor says.