Articles and News

WHICH OF TODAY’S DESIGNERS WILL BE SOUGHT AFTER AT AUCTIONS OF THE FUTURE? | August 22, 2012 (2 comments)

Merrick, NY—Record-blowing prices fetched at the Elizabeth Taylor fine jewelry auction last December as well as for various mega-diamonds have sparked a new interest in the world of luxury jewels sold at auction.

Vintage signed works from the great houses like Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels are auction standards, but when those pieces were made, they were simply the leading designers of their time. So what about jewelry from contemporary designers whose work is available at luxury shows like Centurion, Couture, and JCK? Will it too someday have collectors’ paddles waving?

Much already does. For example, Oscar Heyman has had many pieces turn up at auction. Dealers of super-stones, whether diamond or color, also often sell better at auction than on the wholesale market, and there's more brand-new jewelry than one might expect in auction catalogs, bypassing the traditional manufacturer-to-retailer distribution channel.

The Centurion asked two experts, Alexander Eblen, GG, director of fine jewelry and watches at Leslie Hindman Auctioneers in Chicago, and Beth Anne Bonanno, a New York-based jewelry historian and expert in 19th and 20th century contemporary works, to identify what makes a piece of jewelry appeal to collectors who are willing to pay top dollar.

“It’s very hard to look at designers today and say, ‘that’s the next Boucheron, Mauboussin, or Belperron,” says Bonanno. “People go for JAR (Joel Arthur Rosenthal, an American-born designer living and working in Paris), Wallace Chan, or people like Nicholas Varney, Marina B., Henry Dunay. Michelle Ong (the designer of Carnet in Hong Kong), and I think Daniel Brush is a genius. A lot of his work is very unexpected.

Michelle Ong, right, the designer of Carnet, left, is a contemporary Hong Kong jeweler whose pieces already are in demand at top auction houses. Below, a Bakelite, gold, ruby, and pink diamond bracelet by Daniel Brush.

Eblen agrees that JAR is probably the top name in contemporary jewelers, and his pieces at auction can net a 30% gain up to double the original price paid. “The Ellen Barkin sale was phenomenal for the auction industry, and JAR was an integral part of it. He even got involved in how the pieces were displayed. He’s akin to [Damien] Hirst in the art world in that he [often] goes directly to auction.”

Pieces from JAR, clockwise from left: brooch designed in 1982, with green and pink tourmaline and 37.23-ct. pear-cut diamond. Clip earring with garnet (24.53 cts. for the pair), tourmaline (28.95 cts.), amethyst, and diamonds. Tulip clip earrings, encrusted with rubies, diamonds, a 23.80-ct. blue sapphire, a 21.40-ct. yellow sapphire, set in gold and silver. Photo at top of page, JAR fancy yellow diamond ring set in platinum. All JAR photos, Christie’s in French Vogue.

Eblen also says vintage Tiffany sells well, and especially pieces by Louis Comfort Tiffany himself. He cites as an example a brooch in yellow gold with a fire opal and peridot that was sold by Christie’s in 1993 for $7,000, beating an estimate of $4,000-$6,000. The piece came to Leslie Hindman last year, where it fetched $36,000.

The other artist that’s making news now is Suzanne Belperron, who, he says, was relatively unknown until recently. “You used to be able to pick up Belperron for next to nothing. Now Christie’s is doing a retrospective, and there’s the service from Ward Landrigan that certifies a piece as a genuine Belperron.” No more picking that up for a song!

Early 20th century French jeweler Suzanne Belperron was a relative unknown until recently. Image: Stylesaloniste.com

But designers like JAR don’t wholesale, so their rarity adds to the mystique. Does that mean a commercially available designer, no matter how talented, will never attain this status?

Not necessarily. Bonanno says many commercially available jewelry artists will maintain their appeal—but selectively so. “Even not everything JAR has done is collectable,” she says. Among popular names, there will be pieces that are auction-worthy, but it won’t be the whole run of the line.

Eblen divides the collectable jewelry market into two subsets: one-of-a-kind pieces, and jewelry that isn’t one of a kind but will retain value.

Of the former, he says these are magnificent pieces that really stand out and almost always contain very fine stones, even if those stones need some work (i.e. re-cutting). Of the latter, he says it’s when the designer creates something unusual, distinctive, and that isn’t lightweight. He likes Elizabeth Gage and Elizabeth Locke because they’re known names but not high volume production.

“Avoid the temptation of mass production,” he tells designers who aspire to become collectable.

Still, don’t discount the draw that a big brand has. David Yurman and John Hardy will have appeal simply because of how big they are, says Bonanno, and Eblen says high-volume producers can be collectable if it’s a limited edition piece. But he cautions that it’s important to manage expectations of resale value for popular names: whereas signed Cartier or Van Cleef & Arpels pieces command top dollar at auction—retail and above—a Yurman piece might only recoup 25% to 30% of retail unless it’s a limited edition such as one bracelet Leslie Hindman has at present, a very heavy, rare, gold one.

“Roberto Coin has a museum of pieces he’s created, and those will come forth at some time,” predicts Bonanno. “And Stephen Webster has created some very special pieces. Whether every piece he’s done is collectable I don’t know, but when I look at the house of David Webb from the time he was creating [the pieces] to now, I see similarities in Stephen Webster. Collectors go for the pieces David Webb [himself] created; those who can’t afford a David Webb original will go for the later pieces the house did.”

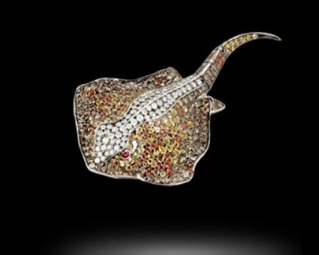

Stingray brooch with yellow and orange sapphires, brown and white diamonds, set in 18k gold pave, from Stephen Webster's Couture collection.

Bonanno also cites names like Paula Crevoshay and Erica Courtney, “because any time you use really great, stellar stones you’ll always draw people. Paula does these fabulous one-of-a-kind pieces, and Erica Courtney’s evolution as a designer is amazing. Her voice is heard throughout her design but she keeps evolving, and someone using beautiful stones and color draws people when the work is signed by a designer with a following.”

Left, Roberto Coin's "Spring" necklace; right, Erica Courtney's "Liz" necklace.

Auction catalog or estate case? What gets a designer into the auction scene? Pushing the creative envelope is one way, of course, but more classic pieces with outstanding stones always will be sought after as well.

Eblen looks for both materials and skill. “For me, it’s important that they are using amazing gems and materials. I want to see stones of a quality and size that stand out, because to sell a designer just on skill alone, they’d have to be a mad scientist or something, like [the late Steven] Kretchmer. But the artist also has to attach a story to the piece. People do buy stories,” he said. Typically, his department asks designers to provide sketches of works in progress, and describe their inspirations for the catalog.

“In fine art, you can’t sell what isn’t proven. But with jewelry, you can take a lot more chances,” he says. Like Bonanno, he believes in the allure of colored gemstones—and is thankful for educated collectors who can appreciate a beautiful spinel or tourmaline as much as a ruby, emerald, or sapphire.

“There’s a whole realm of people who can manufacture an exquisite piece of jewelry. That’s separate, but not less than, an artist who becomes collectable,” says Bonanno. Someone like Daniel Brush or JAR literally can’t think commercially, she explains. These kinds of artists have the luxury of allowing themselves to fail at a design—even multiple times—because they’re not tied to having a collection ready for the next show, and they don’t care if every piece they make is wearable or not. But that’s not a luxury many can afford: she says these jewelers typically have a patron or a sponsor or they’re self-funded, while most commercial designers depend on their creations to pay the bills.

Who are some contemporary designers that appeal to the experts for their collectable value? In addition to his admiration of both Elizabeths, Locke and Gage, one of Eblen’s recent discoveries is Frank Caballero, a Miami-based designer who won both an AGTA Spectrum Award and a Jewelers of America Case Award this year.

Frank Caballero's Spectrum Award piece features 18k white and yellow gold, diamonds, and a Madeira citrine. Photo: AGTA

Like Eblen, Bonanno also favors Locke and Gage, and she cites Ray Griffiths, who does plique a jour enamel, Victor Velyan for his edgy design, and Alex Sepkus because his jewelry has crossover appeal to both jewelry stores and galleries.

Left, Alex Sepkus' "Shield" ring in 18k gold and diamonds; right, Todd Reed's blackened silver bracelet with rough colored diamonds and gems.

“I think Sevan [Bicakci] is very interesting,” continues Bonanno. “Not all of his pieces, but some will become collectable. He takes the essence of his editorial pieces and makes them wearable. The edge is still there, but it’s translated and it’s beautifully made. Part of Katey Brunini’s collection is like that. And Todd Reed and Sharon Khazzam; what they started doing years ago a lot of people are doing now, but it’s the genius of the people who did it first.”

Bonanno makes an interesting point: there are many looks that got so popular they literally become a genre. But does that mean only the original will retain value?

Not necessarily. Explains Bonanno, “It’s funny when people say, ‘that looks like [so-and-so].’ Artists are inspired by other artists, but now we bash people for it. But if I put a Cartier bracelet, a Mauboussin bracelet, and a Boucheron bracelet side by side, could you tell them apart? You can’t, unless you’re very well studied.”

Designer bridal jewelry, however, may have a harder time getting to auction than its current popularity suggests. Bonanno predicts it’s more likely to go the way of the Art Deco three-stone ring—beautiful estate jewelry, but unless it’s got a really great stone, it’s probably not going to be an auction piece.