Articles and News

Why Women Don’t Buy More Jewelry: Too Many Men, Not Enough Color | May 24, 2017 (5 comments)

Austin, TX—12 years after the now-defunct Diamond Promotion Service launched a nationwide study excoriating the typical jewelry-shopping experience, new research from MVI Marketing finds that little—if anything—has changed.

The DPS’s Jewelry Retail Landscape Study took a comprehensive look at what was happening at the nation’s jewelry counters in 2005, interviewing 1,200 consumers, visiting 50 retail establishments, and interviewing 100 brick-and-mortar jewelers. Its verdict was that the industry was doing a barely-average job at enticing consumers to shop.

Now, more than a decade later, as more than 1,000 independent jewelers close each year and the industry is scrambling to remain relevant, it’s still largely relying on the same sales and merchandising strategies that consumers rejected long ago.

MVI Marketing’s research, conducted May 1-5, 2017, did not include store visits or interviews with jewelers, but it did poll 1,056 American females. While the total sample of consumers MVI interviewed was slightly smaller than DPS’s study, MVI’s sample was exclusively female, with 356 more women responding than the DPS study, which polled 750 women and 450 men.

The upshot? The female self-purchase market for fine jewelry remains grossly underserved, and as such, jewelers are cutting themselves out of not only a lucrative customer base now, but also are not satisfactorily sowing seeds for future growth, says Marty Hurwitz, CEO of MVI Marketing and the study’s architect.

“We’re trying to measure or compare the growth in the market or potential consumer market with the ability of our industry to service the market, and there’s obviously a real lag in those two things,” Hurwitz told The Centurion. The market seems to be growing—and female acceptance of purchasing jewelry for themselves is growing—but for the most part the traditional specialty jewelers are still selling to males, he says. Meanwhile, women—who spend thousands of dollars on shoes and handbags in a year—are not being invited to spend that money on jewelry.

In 2005, 30% of respondents told DPS they’d never go back to the last jewelry store they visited, and female consumers told DPS that jewelry shopping simply wasn’t fun. An overwhelming majority (more than three fourths) of women told DPS they’d much rather shop in book, clothing, furniture, or department stores than jewelry stores.

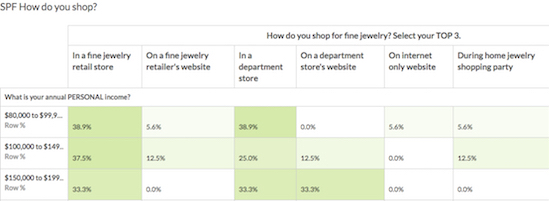

12 years after the DPS's famous Jewelry Retail Landscape Study, MVI's research shows women are as likely to buy their fine jewelry from a department store as they are a fine jeweler. The good news for jewelers is that pure-play e-tailers have less appeal for women shopping for fine jewelry than retailers with a physical presence, even when they buy from those retailers' websites.

In the MVI study, women most often complained that jewelry stores have too many men and not enough color. Diamonds may be a girl’s best friend, but most women don’t want them to be her only friend. They also said:

- “Can’t try on anything comfortably”

- “No style, no fashion”

- “Every store looks the same”

- “They're not talking to me”

- “It's all so white, I need color to accessorize”

“Jewelers, especially of the Baby Boom generation, are males selling to males. It’s a glaring gulf,” says Hurwitz. In addition to adding women—especially young women—to their sales teams, jewelers need to add more color to their showcases. According to Jewelers of America's most recent Cost of Doing Business study, diamonds account for 53% of sales in a typical jewelry store. Colored stone jewelry, by contrast, accounts for 8.9%.

Fashion buyers present a huge opportunity, says Hurwitz. “Some people like Kendra Scott and Alex and Ani are taking advantage of it but others are either ignoring it or unable to take advantage of it or unwilling.

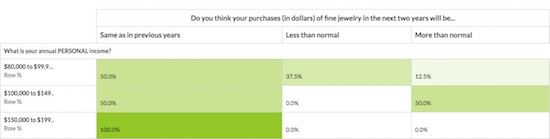

Only one subset of respondents to MVI's study indicated they might shop for jewelry less in the next two years; most women said their purchase plans will be the same or greater.

“Let’s forget about the definition of fine and fashion and costume. Those are out the window. The finer stores probably don’t want to hear that, but that’s the reality of the market,” Hurwitz says bluntly, pointing out that Kendra Scott and Alex & Ani are getting high price points for what we used to think of as costume or fashion jewelry.

It doesn’t mean throwing out the proverbial baby with the bath water but it does require a mindset shift, says Hurwitz. “To a certain extent, male-dominated jewelry enterprises need to understand that it’s not about gemology, it’s about making a profit. As soon as they understand that and stop catering to a male-dominated investment buyer, and shift a section of their business to be more fashion-oriented, sold to and by women, and convey to the female self-purchasers of their community that they are now fashion experts as opposed to just gemologists, that would be a pretty compelling story.”

It doesn’t mean cutting out their male buyers, it opens a whole new market, he stressed. The fashion consumer is, on average, a four-time a year purchase opportunity—and one that would rather do it in the store than online. By contrast, the male gift buyer is a one time a year gift buyer.

“That’s why jewelry turns so slowly and why Blue Nile couldn’t get above the $350 - $400 million threshold and had to go private again. They tried desperately to get to this female purchaser—who it turns out doesn’t want to buy online, and wants an in-person experience! This female consumer would much rather come into the store to buy for themselves, assuming there’s something in the store to purchase.” (Hurwitz isn’t alone in urging jewelers to make gemology secondary in the sales process; veteran sales expert and author Peter Smith says the same thing here).

Hurwitz acknowledges some independents are doing a great business selling to women, but points out the biggest macro-marketer in the industry—Signet—is still primarily marketing to the male gift buyer. “It tells everybody in the jewelry-consuming population that this is what all jewelry stores are like, even if it’s not true.”

When women see mall stores that largely look the same (something else that hasn’t changed since the DPS study) and even freestanding stores that seem to be mainly full of men selling white diamonds, they don’t want that experience.

“Why are retailers hanging on to the old low-margin model? Why not experiment with a new consumer? Don’t get rid of what you’re doing but hire some female salespeople, get some female-designed product and things with color and style that could start at $199.”

High-end jewelers may push back about lower-priced goods, but Hurwitz believes the industry needs to make a concerted effort to bring in younger, less affluent customers who will become the high end of the future.

“For every person willing to spend $15,000 on diamond, there are multiple stores willing to sell it to them,” he says, but not enough selling affordable fashion. “They may start out as middle-income consumers, but they will gain wealth as they age.”

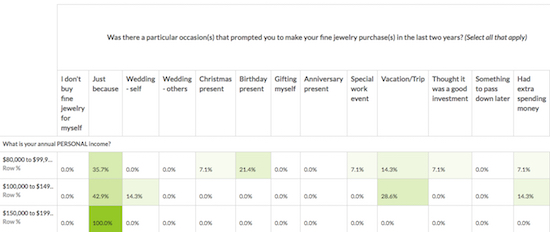

40% of respondents to the MVI study have personal incomes of $80,000 or more and 25% had personal income above $100,000. Across all income levels, the primary reason for purchasing fine jewelry was “just because,” a reason that only grew stronger with each successively higher income group. 35.7% of respondents with income between $80,000 and $99,999 cited “just because” as the primary reason they buy jewelry, but 100% of respondents with income over $150,000 said that’s why they buy jewelry.

Affluent women will almost exclusively buy fine jewelry for themselves "just because." The need for a reason to justify the purchase declines with increasing income (left column).

Hurwitz points to automaker Mercedes-Benz as an example of needing to shift the jewelry-industry mindset: the brand has a major advertising presence at sporting events with a mass audience, something it never would have done a few decades ago.

“The middle needs an entry point to a luxury brand that they will buy later when their income goes up. Other luxury consumer goods have figured this out, but jewelry has been reluctant to develop a product that caters to a growth market, so that when they get older and have more income you can sell them.

“In terms of getting a sense of what they want and what they want jewelry stores to be it’s a pretty clear message,” Hurwitz told The Centurion. “It seems obvious to me and to others in the industry, but to a large cross-section of the jewelry industry there’s still a lot of resistance. I don’t know how much more pain these retailers need to see when 1000 are going out of business in a year, but when there’s enough pain in the retail community that’s when they’ll start to rethink.”