Articles and News

ARE DIAMOND GRADING REPORTS ART, SCIENCE, OR TOOL FOR DECEPTION? | May 24, 2011 (5 comments)

Merrick, NY—Few jewelers would consider selling a significant diamond without a grading certificate, and in today’s information-packed society, few consumers would consider buying one. But what began as a tool for establishing a standard set of parameters to evaluate the quality of a stone—and, by extension, build consumer trust in jewelers—also can break that very same trust.

In an exclusive spot-check survey of prestige jewelers conducted by The Centurion, fully 100% of respondents say they’ve not only observed inconsistencies in diamond grading between different laboratories in the industry, but also lost sales or been put on the defensive by customers questioning the validity of their prices.

Gem grading, of course, is an inexact science and as long as there is a human element involved, there is bound to be some variance. But jewelers told The Centurion there’s a big difference between the subtle variances that might arise from two separate individuals’ opinions, and a certificate that’s significantly—as much as two or three grades—off. Jewelers also believe luxury consumers are smarter than that: when asked if they agree with the statement “I don’t think consumers realize grading can be inconsistent,” not one single respondent agreed.

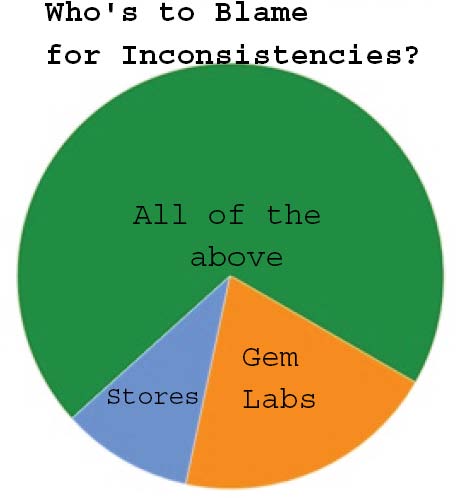

When asked why there is demand for 'soft' grade reports, respondents laid the blame equally across labs, retailers, appraisers, and consumers. The green slice indicates respondents who answered "all of the above." The orange slice represents those who feel soft grading is driven by labs seeking business and the blue, by retailers trying to increase perceived value of their products. The purple and red in the color legend represent "appraisers who can't agree on standards," and "consumers who want a bargain," but neither of these alone were cited as primary drivers of demand for soft grading.

All respondents observed grading inconsistencies by other retailers, as well. 75% say it happens “often,” and 25%, “occasionally.” Not surprisingly, respondents said the worst offenders are companies that bill themselves as wholesale, manufacturer-direct, or other discounters. The mall didn’t fare so well, either: respondents also perceive chain jewelry stores among the most frequent offenders.

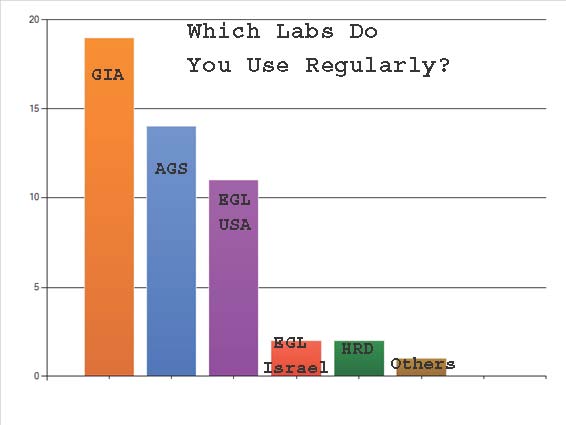

Among the various labs, respondents overwhelmingly trust GIA (Gemological Institute of America) and AGS (American Gem Society) Labs not to “sweet grade;” HRD’s (Hoge Raad voor Diamant, or Diamond High Council, Antwerp, Belgium) lab also rated favorably, though relatively few American jewelers use it.

Respondents were asked to name which labs they regularly use. Most often named were, in descending order from left, GIA, AGS, EGL USA, EGL Israel. The grey bar represents "all other responses." Since more than one answer was allowed, totals equal more than 100%.

Yet even if consumers know better, jewelers say soft or inflated grading wouldn’t exist without demand. When asked who they feel is most responsible for grade inflation—labs seeking business, retailers trying to enhance perceived value, squabbling appraisers, or consumers who want to feel like they “got a deal,” almost ¾ of respondents said all of the above.

Most jewelers require a grading report for all stones over a certain size. A minority (16.7%) insist on getting their own report anyway, so the presence or absence of one isn’t a deal-breaker. The minimum size for most respondents to require a cert was 0.75 ct. or higher, but a small percentage of respondents require them for anything above a half carat. And in the words of one respondent, the labs’ job is to grade it, not evaluate it. “The labs that give ‘appraised values’ with their certifications should be censored,” she writes.

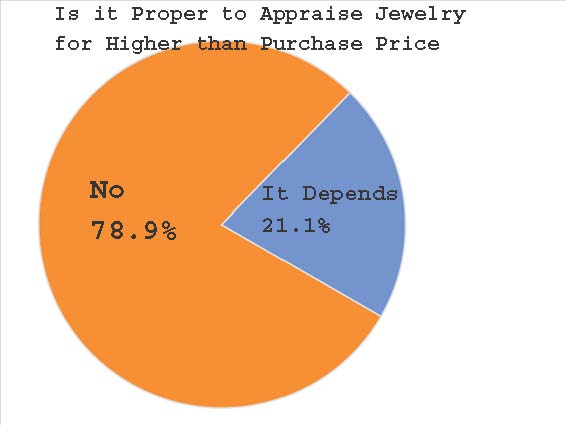

On a related topic, The Centurion survey also did a spot check about some appraisal practices. 63.2% of respondents recall having heard advertisements for jewelry guaranteed to appraise for an amount higher than the selling price. Most, but not all, respondents feel this is deceptive and wrong, but a small percentage said there are occasions when it’s warranted. Writes one respondent, “There are circumstances when an item should have a statement of value higher than the sale price; for example, [if] a discount was given or the item was sold at a price based upon a lower gold market.”

Another respondent takes a practical approach. “[We appraise] a little higher in case of gold prices [going up] and we want to cover ourselves if we have to remake a piece.”

None of the survey respondents, however, feel such an appraisal should be used as a marketing or selling tool. When asked how they handle situations that they think are cases of deception, answers varied from resignation to fury.

While some respondents feel certain circumstances warrant appraising a piece for more than the purchase price (blue slice), the majority feel it's wrong. None of our respondents believe it should be used as a selling tool (purple legend bar).

“I don’t know who to report it to, or if an agency would bother to do anything about it as the practice is so widespread,” was one comment. Said another, “the various state and government agencies see the same ads and apparently could care less.” This respondent also pointed out that consumers who fall for that pitch are the ones who need to feel they got a deal. As most upscale jewelers do, he tries to explain the process and educate suspicious consumers. Some, he said, will learn eventually and others never will. Another respondent, however, feels upscale jewelers do have an opportunity to build trust this way. He successfully helped a customer verify the true value of a piece purchased from Costco—he writes that the warehouse club apparently reimbursed the customer for the cost of his appraisal.

All Centurion survey respondents said they provide appraisals with the jewelry they sell. 83.3% appraise it for the exact purchase price; the remainder, for keystone value (presumably having sold it for less.)