Articles and News

All In The Family: A Business Perspective | November 29, 2010 (0 comments)

Philadelphia, PA—You can pick your friends, but you can’t pick your relatives, the old saying goes. But if you’re in business with your relatives, that adds a whole new dynamic.

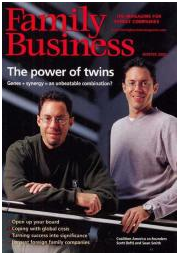

Barbara Spector has been the editor-in-chief of Family Business magazine for more than 10 years, and in this exclusive interview with The Centurion, she discusses both formulas for success and common misconceptions about running a family business.

The Centurion: As the editor of Family Businessmagazine for more than 10 years, what five most common concerns have you seen recur among family business owners?

Barbara Spector: The first rule is to remember that every family is different and every business is different. What works for one doesn’t necessarily work for another, and many businesses have ignored traditional maxims and been hugely successful. That said, here are some of the most common issues:

- Family members need to put their family issues aside and view each other as co-workers. Parents can’t view the children as someone whose diapers they changed and who don’t know anything; siblings need to have a division of labor according to what’s going to move the business forward.

- Choose a successor that’s right for the business. It’s not necessarily the oldest child, or even a family member, if that’s what’s right for the business. Also, choose a successor who’s the right choice not only for now but also for the future.

- There needs to be adequate preparation for the retiring senior generation to have income in retirement. If the business has to take out a loan to support them, that isn’t good. They [the seniors] need to either be proactive about planning for their own retirement like anyone else [in a non-family business], or the next generation can buy the business rather than have it gifted. In many ways, that’s the best scenario because then the successive generation has skin in the game. But there also are plenty of businesses that have been successful where it’s been gifted.

- A family business needs to innovate and look toward the future, which means getting new blood. Either hire outsiders, send family members out to work in other businesses for a while, or have a board of directors with some outsiders on it. This will help prevent the owners from being too invested in “how it’s always been done.

- The third generation is a hugely pivotal point—and often a major stumbling point—for family businesses. By now the family has branches and there are cousins to consider, not just siblings, and cousins are different than siblings. They haven’t been raised together, and they weren’t all raised the same. This also is the point where a business may have more family members than places to put them, or where some members of the family have interests outside the business but still have an ownership stake. Are there shareholders that don’t work in the business? What if one second-generation owner has two children who work in the business and another has five who don’t, but they’re all equal shareholders? This creates a huge imbalance, and this is the point where family-business experts start to talk about pruning the family tree through buyouts and such. And if you get beyond the third generation, it starts to get really complex, so even if you’re still the first generation getting ready to transition to the second, realize that this is going to be an issue eventually and you need to be proactive about it. You need to be really careful and try to anticipate any scenario that might arise and have a plan for dealing with it. Luckily, there are many family business experts that can help with this.

The Centurion: Have any of these issues changed in the past two or three years?

Barbara Spector: Well, the economy hasn’t been very good—news flash—but that hasn’t really changed the basic issues. What it has done is raise some new issues, or given new significance to old issues, like who is going to work in the business. For example, what if a family member loses his or her job elsewhere and hasn’t been able to find another? Do you bring that person into the business? It can be a problem if there isn’t a spot for them, or if their skills are wrong, or if they’re not that interested in the business and just doing it because of the situation. What if you have a policy about who comes into the business but they don’t fit the parameters? What are the implications if you waive the policy, or would it be better to help the family member in other ways, such as financially or help with their health insurance?

Companies that have done well generally operate with the mantra “Cash is King.” The senior generation (aka “Greatest Generation”) tends to be very conservative. They’re frugal, they conserve cash, they don’t borrow unless they have to, and so forth. It’s a good thing, too, because it’s very tough to get money from banks. Lots will require a personal guarantee, which can be a real problem in some industries right now, such as construction. But sometimes a business just has to borrow money, if they’re going to open a new location, invest in major equipment, and so forth.

Some will find cash in other ways than traditional bank loans, such as mezzanine financing or private equity. But that has its own issues, because with private equity you’re bringing a nonfamily member into the business. And if it doesn’t produce the returns [the equity partner wants], it can be very bad. Some companies have become overleveraged, but other companies have been able to take advantage of opportunities. For example, P.C. Richard & Son, a fourth generation appliance retailer, bought a number of former Circuit City locations and expanded.

The Centurion: Are there similarities in how different companies deal with the same issues?

Barbara Spector: Every company and every family is different. All have ways they get along—or not. The best have figured out how to resolve disputes, others will just blame each other [for the problems.] That’s why family-business psychologists will always ask a family to talk about why they’re in business together, why they stick together as a family.

Realize that you have to teach the next generation about risk. You have to teach them early what those figures on the balance sheet mean, teach them about investment, and do all the stuff that nobody makes time to do. This [a slow economy] is a good time to do all that, so that when the next Madoff comes along, you can avoid it.

The Centurion: What, if any, differences have you observed between a business serving an affluent clientele, vs. one targeted to a mass clientele? Also, successful business owners are likely to be affluent themselves. Do you get a sense of their attitudes about spending (other than reinvesting in the business) and do these attitudes change with each successive generation? What should a luxury retailer do to court them?

Barbara Spector: At FB, we deal with issues at the nexus of family and business—we don’t get into the nitty-gritty of marketing or daily operations, so I’m not able to speak to this directly, nor about the spending habits of the business owners.

But I can address the dangers of entitlement attitudes and overspending in later-generation family members: we see it often. Either the family member feels entitled [to live lavishly], or there’s pressure from a spouse to keep up with other siblings in the business. ‘Why does your brother/sister have a BMW and we don’t?’ But what has that sibling done in the business [to earn it]?”

Like I said earlier, companies that have done well generally operate with the “cash is king” mantra. And especially in times like these, businesses that have good cash reserves are in a better position to survive long-term.

The Centurion: It’s a popular belief among pundits that many family businesses don’t survive third-generation ownership, though jewelers seem to be an exception, as we have many fourth-, fifth- and even sixth-generation companies still in operation. Have you observed this maxim to be true, or not?

Barbara Spector: There is a very real pivot point, as we discussed earlier. Conventional wisdom says that slightly fewer than 30% of new businesses make it to the second generation, 12% make it to the third, and only 3% to the fourth. These sound like grim numbers, but the average lifecycle of a [nonfamily] business is only 25 years, which is one generation. Among all businesses, 50-60% fail within the first five years and only 25% reach 10 years, so the family business statistics are quite good in that respect.

The Centurion: So looking at those statistics, jewelers have really done quite well. Even with the current net loss of about 800 or so retail jewelers per year, only a fraction of those are actual failures.

Barbara Spector: If the business doesn’t continue, that’s not necessarily bad. Maybe the family sold it and is using the money to do something else together, such as a philanthropic foundation, or they’re pursuing another entrepreneurial venture. They’re still working together as a family, just not in that business. The issue isn’t whether the company is in business, but whether the family is happy and harmonious.

On the downside, a lot of relationship issues occur because the next generation is running the family business but they’re miserable. They don’t want to give up the legacy, or maybe their parents are still hovering in the background, but they’re not happy being in the business.

The Centurion: Are there any other observations can share?

Barbara Spector:Family business owners are very loyal, sometimes to a fault. They’re loyal to the business, to the community, to the family, to long-term employees, sometimes even when it’s no longer right.

Succeeding generations should work outside the business, long enough to be promoted at least once and preferably twice. They gain respect from members in the business, and they also build confidence that they can succeed outside the business. But, lots of family businesses also succeed without having done this. In those cases, the next generation usually compensates in some other way—either they’ve worked in every position in the business from the bottom up, or they’ve gotten an executive MBA, or they’ve joined local business organizations, something to give them an outside perspective.

Why do people like family businesses? I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know, but it’s the connection to the community, not just a faceless corporation. Even S.C. Johnson—people don’t know Fisk Johnson personally but they feel a connection. Family business is the backbone of American business. It’s community, it’s philanthropy, it makes sense that consumers love that.