Articles and News

DIAMONDS OR MUTUAL FUNDS? HOW TO HAVE THE INVESTMENT CONVERSATION WITH YOUR CUSTOMERS | March 21, 2012 (0 comments)

Merrick, NY—If it hasn’t happened yet, it’s likely to at some point: a good customer sees an advertisement for diamond investment, and he wants your opinion.

What do you say? On one hand, you don’t want to steer him toward something that might be highly risky—especially if you remember the first go-round of diamond investing in the late 1970s and early 1980s—but on the other, your business is built on the lasting value of precious metals and gems.

It’s a conundrum. And even experts don’t agree whether it’s a good idea or not.

A new fund, IQ Physical Diamond Trust, is under application with the SEC , while diamond investment sites such as Pinnacle Diamonds offer a laundry list of plausible reasons why diamonds would be a good investment, all based on the laws of supply and demand. Their points are valid:

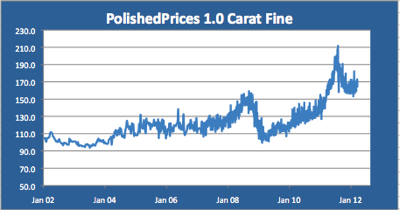

- First, diamond values have increased—50% over the course of 10 years, according to PolishedPrices.com. And historically, diamond prices have been far less volatile than precious metals.

- Second, diamond supply is finite—it’s no secret in the industry that many of the older mines are nearing their productive end, with no new major finds coming online to date.

- Third, diamond demand is indeed growing in India and China (as well as Russia and the Middle East).

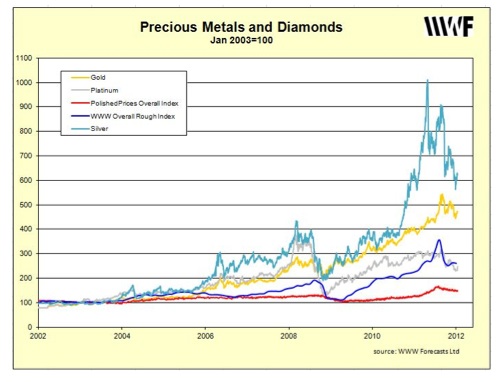

Above, a chart from PolishedPrices.com, showing the index of prices for one-carat "fine" diamonds (G VS2 or better) for the last 10 years. Below, a chart from WWW Forecasts Ltd. shows that polished diamond prices (red line) are far less volatile than either gold (yellow line) or silver (aqua line). Platinum (gray line) is less volatile than the other metals but more than diamonds. The blue line shows rough diamond prices, which move independently, and sometimes at odds with, polished prices--but they aren't up for investments yet.

So these facts, all true, do make a compelling argument for diamonds as investment—whether bought from an investment-focused site like Pinnacle, which essentially competes with jewelers because it delivers the actual stones to the customer—or buying loose stones from a jeweler.

But if an investor is going to put money into diamonds, it stands to reason that at some point in time he’ll want to take it out and use it for something else—and that’s where the tricky part begins.

Ben Janowski, a longtime consultant in the industry with a background in both diamonds and retail, is not a fan of diamond-based investment.

“There is no instant, liquid market for diamonds. There is for gold, platinum, copper, and even pork bellies, but not for diamonds,” he says bluntly. “Today, dealers all know how to cut Ideal or near-Ideal, and how to get GIA certs, so that’s flattened the playing field somewhat, but diamonds are not fungible and they don’t fit the commodity model. They never did.”

Janowski maintains that if diamonds had been able to fit the commodity model, there would have been diamond investment funds in existence long ago. In 1980, the diamond market boomed, prices shot up, and then everything collapsed—but if a legitimate opportunity for diamond investment did exist, it still would.

“The New York Stock Exchange didn’t disappear in the aftermath of 1929,” he says.

Richard Platt, a director of PolishedPrices.com, an independent diamond information platform in the United Kingdom, disagrees. He believes there’s both opportunity and need for a proper diamond investment fund.

“The diamond industry as a whole could be better off with a proper [government] regulated diamond fund, because it can benefit quite a lot from investment dollars,” he told The Centurion.

But the key word is “regulated,” emphasizes Platt. He stresses that before an investor puts so much as a dime into any diamond fund, wait until it gets full regulatory approval, with independent and transparent pricing, and clear disclosure of what the transaction costs are.

“Without regulatory approval, you’re basically lending people money to speculate,” Platt says. In a properly regulated fund, investors can put money in and take it out at any time, just like a mutual fund, but in an unregulated fund, if everyone wants to pull money out at the same time, the fund may not be able to pay out.

Russell Shor, senior industry analyst at GIA and a diamond industry observer for more than 25 years, says diamonds do hold their value against other luxury goods categories, such as handbags or shoes, where an item can lose much, if not all, of its value after hard use. That’s not the case with a diamond, which as jewelers know is a good selling point at the counter. But historically, Shor says, the only stones that offer significant return on investment are the ones that are extremely rare—either mega-stones of 10 carats or more, or some intense fancies, mainly pinks and blues.

Basic one-caraters? Not so much.

Janowski says a couple that bought an engagement ring 30 years ago can clearly see their diamond is worth a lot more today than what they paid for it—but if you run the increase up against the inflation calculator, it’s not quite as much of a gain as it first appears.

And it’s also predicated on what they plan to do with the diamond. While a jeweler may be willing to give the couple a generous trade-in allowance to upgrade the ring, that’s a different transaction than an investor looking to cash out.

“Generally, an individual buying a stone for investment, unless it’s in the mega-carat bracket, is going to buy at retail and sell at wholesale,” Shor says, pointing out it’s about a 30% price spread. He also added that in really lousy times when stones drop in price, it’s rarely a gentle float down; it’s usually a plummet off a cliff.

One is reminded of a scene in the 1993 movie Schindler’s List, where one of the characters is trying to procure a pet poodle for his mistress. Too bad she doesn’t want a diamond necklace, he’s told. Diamonds were quite plentiful during the war—but a poodle was a lot harder to find.

“In a real crisis time, diamonds are going to be illiquid,” says Shor. “Stones [value] will come back—probably—but if you need the money from it [at that time] you’re not going to get it. People who are distress-selling jewelry traditionally don’t get a good return on it, he says, because jewelers can buy wholesale from their suppliers so the only way a diamond seller can make a stone more attractive is to sell it below wholesale. Plus, he adds, even high quality one-carat stones are pretty common. They’re certainly rare compared to one-pointers, but there’s still a world of choice out there.

“Go on the Rap list and see how many dozen one-carats are on there, then look at how many 15+ carat stones are there,” he says. He cites the recent Baselworld fair as an example: top stones held firm on prices, but for anything less, a dealer who needed the money had to settle for what he could get.

Experts also are divided about the importance fungibility plays in a commodity market. Does it matter that one bar of gold is exactly the same as another, while each diamond is individual?

Janowski believes it does—and that the lack of fungibility also means added labor cost to determine each diamond’s respective value. But according to Platt, no, it doesn’t. Third-party certificates, such as GIA, have brought a degree of transparency to the market that’s necessary to trade as a commodity, and diamonds are no less fungible than pork bellies or cocoa beans, he says. “Every pig is different and every cocoa plant is different, just as every diamond is different, but organizations like the GIA have eliminated a lot of these issues.”

Shor says it all still comes back to rarity: it matters for mega-stones, and less for average stones. “Someone who’s spending millions of dollars is pretty particular about their stone,” he says.

So what should a jeweler tell a customer who wants advice about investing in a diamond?

People who are buying diamonds for investment, rather than as a piece of jewelry, expect to get their money back, says Platt, and that’s what a jeweler needs to keep in mind before offering any advice.

But even at auction, a mega-stone may not be an easy sell, warns Janowski. The auctions take a 10-15% commission, and, as he puts it, “they want Liz Taylor—provenance—not just another piece of jewelry.” He illustrates the case of a 7.5-ct. M VS2 stone with a good cut that he recently showed to an auction house—and was told to take it to a dealer.

And a dealer, he emphasizes, is going to buy it at a price that still allows him to turn around and sell it at a profit. “It may be a very short margin, but it’s still going to be a margin,” says Janowski.

Says Shor, “If he wants the stone as an object of beauty to appreciate, then buy it. If he wants it for investment, apprise him of the risks. It’s tough to lose a sale, but at least you keep your credibility.”