Articles and News

EDITORIAL: HOW DIAMONDS WENT FROM WHIPPING BOY TO ROLE MODEL | January 11, 2012 (0 comments)

Merrick, NY—When the conflict diamond issue broke open in 2000, the horrific images of Sierra Leonean amputees sent chills up the industry’s collective spine. Twelve years later, African mineral wealth still is being used to fund brutality and conflict, according to this article in Time magazine.

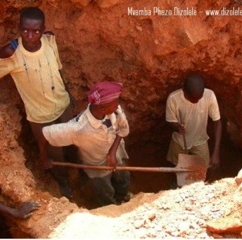

The difference is it’s not diamonds, it’s tantalum, tin, and tungsten—and gold, too. But tantalum in particular goes into the making of smart phones, semiconductors, and other things we can’t live without, and the DRC’s vast resources of it and other minerals have not only supplied phone parts but also funded militia groups whose armed conflicts claim the lives of millions.

“After years of human-rights organizations’ decrying the indifference of technology companies to the people who dig for their minerals, Congress last year voted to try to halt the conflict-mineral trade from [Democratic Republic of] Congo, in a provision buried deep in the Dodd-Frank financial reform act,” says the article.

Where have we heard this before? Substitute jewelry for technology and Tony Hall for Dodd-Frank.

It does sound eerily familiar but there’s one big difference. Socially conscious consumers could and did justify eschewing a diamond, but I suspect that if 60 Minutes were to do an episode about conflict cell phones, most of them would feel badly about it, but not enough to give up texting and tweeting. And the media isn’t bashing the IT industry like it did the jewelry industry. Perhaps there’s a vested interest in ensuring consumers can read their news on mobile devices?

The jewelry industry was taken to task—somewhat rightly—for its slow, deliberate response to the conflict diamond issue. More than three years passed between the first major reports of brutality and the implementation of the Kimberley Process. It took far too much time to satisfy the watchdogs, but gaining cooperation from all the necessary parties wasn’t going to happen without discussions and compromises. The KP emerged a flawed document, but it was better than nothing.

Now, a little-known provision in the Dodd-Frank bill requires American public companies to independently audit their supply chains to ensure no minerals come from mines linked to militia groups in either the DRC or neighboring countries.

It’s very Kimberley-esque. While the diamond industry later realized the extent of Kimberley’s flaws—its limited language stops diamonds from rebels but allows bad dictators to run amok—it still serves as somewhat of a model for the tantalum producers’ custody chain. The objections are the same, too—namely, figuring out exactly which truckload of tantalum is “conflict” and which is clean. Without leaving the DRC altogether and sourcing from other places like Australia, Brazil, and Canada, technology industry experts say it’s almost impossible to tell because the conflict extends to so many areas where there are mines.

The IT industry is struggling with the question of whether U.S. intervention in the form of trade embargoes will help rout the rebels and settle the conflict—or just make things worse for the workers who barely subsist now. Sound familiar again? See “artisanal mining, Sierra Leone” or “Marange region, Zimbabwe.” Or, conversely, if Congress or the U.S. IT industry does place a ban on all DRC minerals, will countries like China that have already demonstrated how little they care about human rights simply come in and take up where the Americans left off? Cheap cell phones rely on cheap tantalum, so sourcing it in non-cheap nations like Brazil, Canada or Australia will make the phones a lot more expensive and U.S. consumers won’t like that. So short of banning all Chinese-made technology from U.S. import, the tainted minerals simply come in the back door instead of the front.

But let’s look at the upside. Diamonds have wrought much good for Africa, and the IT industry has an opportunity to do likewise. Botswana, of course, is the poster child for African economic development—since diamond mining began there it’s shot up from being almost as poor as Haiti to a per-capita income rank of number 84 in the world—higher than Mexico, Turkey, China, Thailand, and many other countries.

For all the perceived negatives associated with its structure as a cartel, De Beers has demonstrated a long-time commitment to both ecological sustainability and ensuring political stability, not to mention the role it played in Botswana’s transformation. Meanwhile, many of its larger sightholders like Lazare Kaplan, Rosy Blue, Julius Klein, and Leo Schachter now have factories in Africa to keep more of the economic benefit from diamonds closer to the native communities around the mines, while GIA has invested heavily in a diamond grading facility in Botswana and implemented education programs there and in South Africa and Madagascar.

The IT industry is just getting on board with similar programs, such as Motorola Solutions’ Solutions for Hope, which launched in July with the goal of cleaning up its supply chains in Africa and elsewhere, says the Time article. Hewlett-Packard and Intel have joined in.

But the jewelry industry is far ahead. Aside from the individual efforts of De Beers and its sightholders, African diamond-producing nations have a new champion in the Diamond Empowerment Fund. The charity, founded five years ago by hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons, is focused on funding education in those nations, with the belief that a hand up is better than a handout. DEF is a global organization, with some major muscle—De Beers, Rio Tinto, Sterling Jewelers, Richline Group, Rosy Blue, Leo Schachter—behind it. Last week marked DEF’s inaugural Good Awards, a high-wattage event in New York celebrating individuals and companies in the industry who have demonstrated a commitment to good corporate citizenship and sustainability. Honored at the first annual Good Awards were De Beers and Diamond Trading Company CEO Varda Shine, Rio Tinto Mining and its U.S. manager Rebecca Foerster, Sterling Jewelers Inc. and its vice president and DMM Ed Hrabak, and as a “newest and brightest” star to watch who’s also committed to sustainability, Ivanka Trump.

It was an event that put DEF firmly on the map in the U.S. jewelry industry. Meanwhile, when it comes to dealing with thugs who would exploit Africa’s mineral wealth for their own gain, the diamond industry—while not perfect—has set a good example to follow.