Articles and News

Exclusive! Q&A With Jonathan Dorfman, On The Luxury Market And Why Dorfman Jewelers Closed Its Doors | April 20, 2016 (0 comments)

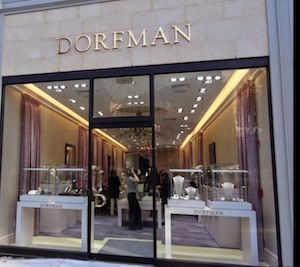

Boston, MA—When third-generation überluxury jeweler Dorfman announced its closing barely a year after undergoing extensive—and expensive—remodeling of its tony Newberry Street location, the high-end jewelry industry experienced another collective shudder as the already-shrinking number of independent jewelers contracted by one more.

But unlike many other Baby Boom age jewelers approaching retirement, the Dorfman brothers’ decision to close the store had nothing to do with their own lifestyle, and everything to do with their customers’ changing lifestyles. In an exclusive interview with The Centurion Newsletter, Jonathan Dorfman candidly talks about changes in the luxury industry and why he and his brother, Douglas, decided to exit the business their grandparents founded.

The brothers took an entrepreneurial route into the jewelry industry. Shortly after college, Doug founded Connoisseurs, a company that makes consumer jewelry-care products, and he and Jonathan grew the company into a global leader in the category. The brothers took over the luxury store after their father got sick, but their primary business still is Connoisseurs.

Jonathan Dorfman shared his thoughts about the family store and the changing market for high luxury jewelry:

The Centurion: What led to your decision to close the store?

Jonathan Dorfman: We closed the store for a number of reasons. Most importantly, it became distraction to our main business, Connoisseurs. But we also believe that the luxury jewelry industry is undergoing some difficult times and we don’t believe things will get appreciably better in the short term. Given that and the demands of our other business, we thought it made sense to focus on our primary task.

Centurion: When did you begin to notice the luxury business had changed?

Dorfman: There are many, many reasons. I think the luxury industry in general has a problem of relevance to the consumer. [Ultra-high] jewelry represents a lifestyle and a set of fashion choices that North American and European women don’t follow anymore.

First, one can live and work in a suburb, so there’s less need to go into a city. There’s a proliferation of stores bearing luxury names in malls around the country; there’s no reason to go see Gucci or Armani on Madison Avenue or Michigan Avenue or Rodeo Drive when you can get those same products in a luxury or quasi-luxury suburban mall.

The proliferation of [luxury] brands everywhere you look from duty-free shops to shopping malls to the Internet is quite the paradox. The publicly held companies emphasize the exclusivity of those brands, but proliferate their brands in places where perhaps they don’t belong. I think the Internet has furthered that trend and made shopping not exciting anymore.

A second reason has some ironic overtones. Because women are working, they have disposable income they control, but in the workplace, much high jewelry is unnecessary and not appropriate. The workplace is informal—neither men nor women need to dress up the way they did a generation ago.

I’m in touch with lots of up-market women. The ones who work need their jewelry to be somewhat sedate, and the ones who don’t [work] tend to revolve their lives around their children. They’re not the shopaholics they’re portrayed to be.

Centurion: But aren’t there still important events to get dressed up for?

Dorfman: Here in Boston, if you look at what women actually wear at charity balls—not the people who are paid to wear Chopard or Van Cleef, but the ones who pay tickets and are on the board of the museum or orchestra—they dress like the curator, not like the people who are photographed at the Met Ball [in New York]. This is the same all over. The fabulously rich people who are on these boards are affected by these cultural trends. To live one’s life luxuriously and nicely you simply don’t need the stuff like you did a generation ago.

The whole Oscar glamour parade is fun to watch on television and there are articles in the luxury magazines about what this star or that is wearing, and undeniably it promotes the brands that lend jewelry, but I don’t think it sells a lot of jewelry. It might sell some lower end things, but it’s not selling jewelry from $50,000 to $150,000.

Centurion: What else is changing?

Dorfman: General price deflation or lack of discipline in pricing because of the Great Recession. In 2008-2010 everything was on sale; you just had to ask. I think that encouraged the consumer to realize that the pricing structure that had been somewhat sacrosanct was elastic. That trend got further momentum by the Internet. There was a plethora of product from scarves to watches to jewelry to furniture at one’s fingertips and you could get what you wanted at the terms you wanted. The competition for the luxury dollar has become so severe. If what you wanted was the kick from buying something, the kick was available in relatively small retail outlets, but now it’s available 24/7 at your computer.

Centurion: But the high end of the industry has done quite well in recent years, significantly better other sectors.

Dorfman: The price points for jewelry that is appropriate [for today’s consumer] are much lower. There the branding becomes very tricky: if you’re selling a $3500 ring with a brand vs. a $4200 better ring with no brand, it becomes enormous competition. The business has changed so fundamentally, so radically, that we don’t see it getting better. Those trends are here for a while.

I went to three benefits last week and I’m always struck by how rich people regard expensive jewelry as costing much less than what up-market jewelers carry. They’re willing to spend $80,000 on car, but they look at a watch for $8,000 and blanch. They think $7500 to $15,000 is a lot of money to spend on jewelry. $15,000 gets a certain amount of jewelry, but it’s different from what [ultra] luxury jewelers have been selling for a generation.

Now this doesn’t apply to bridal—that’s an entirely different issue. But otherwise, what the [ultra high] industry has isn’t of personal, emotional, and cultural importance to the consumer. Shoes are relevant because you have to put something on your feet. Handbags are because you need something to put your stuff in, and automobiles are because you’re driving every day.

Centurion: Did your extensive remodeling attract any more of the luxury customers you sought?

I think the remodeling helped. I think it was necessary, and the aim was to make what had looked like a private men’s club look like an inviting place where people didn’t feel as if they had to know the owner. I thought it was a successful redesign and we got terrific reviews for it. The decision to close the store had nothing to do with the remodeling. There are always a few details you could do differently but fundamentally the problems we faced are being faced by the industry as a whole.

The interior of Dorfman after remodeling it from a clubby atmosphere.

Centurion: Such as?

Dorfman: The Chinese consumer is now quiet and that’s a very big part of the story. That consumer for years masked the fundamental problems of the luxury business.

Many [ultra-high] luxury stores like our own have depended on the Chinese, Russians, and Arabs, and all three of those markets are under pressure. Jewelry is very relevant for them, and that demand masked some of these fundamental problems and allowed the industry to make a lot of mistakes it might not have made otherwise.

Centurion: What about shifting to a lower price point and more casual looks?

Dorfman: Yes, that’s fundamental to our story. When we remodeled and tried to give a more open face to the public, we restocked the store and the emphasis was dramatically away from important jewelry and towards wearable everyday jewelry.

I think by the time we closed the store we sold every piece of that jewelry. There wasn’t a piece left in the store.

Centurion: So doesn’t that prove you were on the right track?

Dorfman: Two points undercut that: Even though the jewelry was casual, it still wasn’t as relevant to the lives of these women as we would have liked, and two, the fact that we were able to sell it all at highly attractive pricing confirms my view that the consumer will refuse to pay the price that makes it viable for you to work at a profit.

The Internet and supply and demand has created a situation where the consumer can always wait. People know that supply outpaces demand and that changes the terrain. That raises an interesting point because luxury is rarity, but when Armani is in the Paramus [NJ] mall and you can get Cartier in the King of Prussia [PA] mall, you’ve cut the rarity that is the very essence of luxury. That’s not going to change as long as the mass class brands are owned by public companies that dictate a certain level of profits. I can’t think of a brand that’s really been able to maintain its exclusivity. Patek Philippe has, but they’re privately owned so that’s different.

Centurion: But if luxury is more accessible, doesn’t that mean more people will buy it?

Dorfman: It is a good thing—in every way—that great design is available to a lot of people. That’s one of the wonders of democratic capitalism. When fashion became industrialized it meant you didn’t have to be rich to get clothes that fit. Suddenly good fit was available to a guy without money. I’ve always objected to the idea that ‘now the masses have this it’s no good for us.’ The safety features of a Mercedes-Benz are now available to a guy with a starter car, and that’s a great thing. But the long-term trends are going to affect the jewelry business, and that’s made it very hard to attract high spenders because of the availability. The advertising for the luxury brands is quite good, the quality is good, but it’s over-distributed. I don’t know where it’s going, but right now it’s in a very difficult period.

Centurion: Did you consider any alternatives to closing?

Dorfman: There really were no alternatives. For the kind of business we’re talking about, the only kind of people who are doing this or have the money to continue to do it are the big brands, and they’d want to have their own mark on the store, not ours. These businesses need to be family run, so no other entrepreneur would want to have my name on the door.

Centurion: What was the most successful aspect of your going-out-of-business process? Did you use a service?

Yes, we used Gordon Brothers, right here in Boston. I think it went well because we had a very good name in the city for many years, so when we did offer discounts it was an attractive proposition because we had jewelry of high quality that people wanted at a discount. Had we not stood for something all these years, the discount would have been like pushing string and people wouldn’t want it. That I owe to my parents. The key is when you have a good reputation and you want to sell at a discount, it will work.

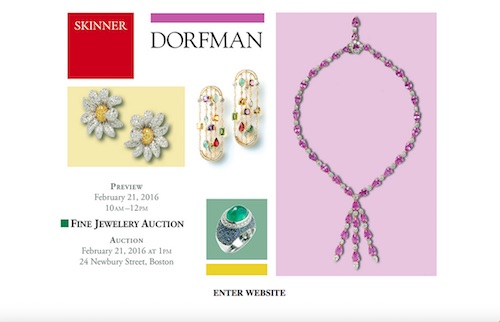

Centurion: You also took the unique step of liquidating through an auction house. Was that financially motivated, or to maintain your image to the end?

Dorfman: We did the auction the last day. It was a relatively small part of the total liquidation. I don’t think it had been done before and I thought it was useful. We used Skinner, a local auction house. We knew the jewelry curator there for years, so it was comfortable. It had nothing to do with image—we wanted to sell the jewelry. Dealers attended, and some very well heeled people, and some bottom feeders.

Toward the end of the liquidation, the Dorfman website opened to this page highlighting the Skinner auction.

Centurion: With many of your jeweler peers in similar situations—close in age to you with a customer base that’s also aging or changing—what would you recommend they do if they don’t want to retire or close?

I had many conversations in Basel—there are so many like this! But I’m not smart enough to tell anyone else what to do. People say, ‘Well, I’ll [retire and] go sell big stones.’ Well, people don’t really want them. We sold a huge stone to a friend of ours and his wife won’t wear it. She feels it’s inappropriate.

Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart aren’t coming back, and neither is Jackie Kennedy, or the 1980s and Nancy Reagan. Hollywood doesn’t make Ginger Rogers/Fred Astaire movies anymore, there’s no longer ballroom dancing with elegant gowns. That’s just how it is, and as soon as everyone understands that, the [really up-market high-end] industry can regain some equilibrium.

I’m not lecturing people—there is tons of beautiful jewelry that is perfectly appropriate for people’s lifestyles, so if I were smarter and more effective I would have done better at it, so I wouldn’t presume to advise anybody!

Centurion: Going forward, where do you see the future of luxury jewelry? How does one sell “forever” to the H&M generation that turns over clothing every few months and replaces tech gadgets every year?

Dorfman: Patek Phillippe’s ad campaign about preserving it for the next generation is genius. And bridal is totally different, of course. But I’m hard pressed to find other examples of that. As long as mass brands are dominating, they’ve got the stores, and it’s very hard for designer to break through. How do you get the distribution? If you’re a wildly talented person making jewelry from $2000 to $4000 and it’s totally appropriate for what we’re talking about, how do you get the distribution? Very expensive to advertise, very hard to put in malls, what is the distribution strategy? Then rich women come in and say, ‘do you have Van Cleef?’ because they saw an ad. I’m friends with a lot of these designers, and I just tell them to think small and keep doing beautiful stuff.

I take no pleasure in this. This is a wonderful industry. I love the industry, I love the people, and I’ve made many friends in it, but like anything else: there’s a golden age and things come and go. I think we’re in for a period of difficulty and I think if I had to sum up, the whole luxury movement that was once exciting is now exhausted and I don’t think anybody knows how to fix it. I certainly don’t have the answers!

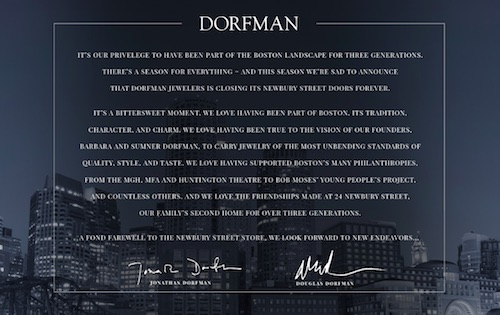

Dorfman's website now opens to a farewell letter.