Articles and News

Luxury Leaders Discuss Sustainability At Bloomberg Conference | November 26, 2019 (0 comments)

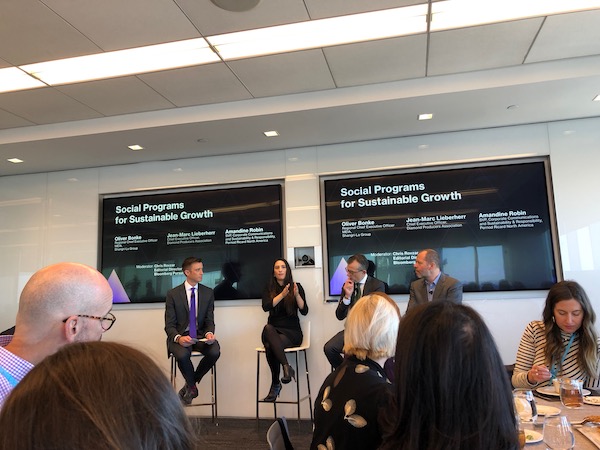

New York, NY—At a special VIP luncheon preceding the Bloomberg’s The Year Ahead: Luxury conference on November 21, Jean-Marc Lieberherr, outgoing CEO of the Diamond Producers Association, joined Amandine Robin, a senior vice president at Pernod Ricard North America, and Oliver Bonke, regional CEO for the Shangri-La Group, for a discussion about sustainability in the luxury market. The talk was moderated by Chris Rovzar, editorial director of Bloomberg Pursuits, the Bloomberg conglomerate’s luxury publication. DPA was one of the title sponsors of the event.

Amandine Robin began by explaining the evolution of Pernod Ricard’s social agenda.

“It used to be just responsible drinking, but we wanted to go beyond that. We created a sustainability roadmap based on four pillars that touch the entire [spirits] business from grain to glass.”

The beverage company taxes itself $100 per foot of carbon use, which it puts back into its communities.

“Linear production creates waste, but in circular production the waste is used back,” said Robin. Pernod Ricard began to look at its production with the circular concept. For instance, the waste from the distillation process can be used as food for cattle.

“It’s not only our employees but all who are impacted throughout the journey. The farmers who work with the grains, the distributors, the employees, right down to the bartenders who put the glass in front of the customer.”

Another initiative is a responsible hosting program, and a website for parents to talk to kids about alcohol abuse.

From left: Chris Rovzar, editorial director of Bloomberg Pursuits; Amandine Robin, Pernod-Ricard North America; Oliver Bonke, Shangri-La Group; Jean-Marc Lieberherr, outgoing CEO of Diamond Producers Association.

Jean-Marc Lieberherr then addressed diamond mining. While his presentation contained material familiar to the jewelry industry, it was new to the greater luxury market.

“You don’t choose where to mine, you go where the diamonds are,” he said. “All [diamod mines] have communities that depend on the land, which is usually pristine, and you also have governments that want a part of the share.”

Diamond mining means employment in these remote areas, he explained. “90% of [the mine] employees are from area, and the mine is going to be there 30, 40, 50 years. You have multiple generations working at the mine.”

But, he said, eventually the mine will close and there has to be something for the people to do later, which is why mining companies put such an emphasis on providing education and supporting schools, and teaching residents other skills so they can do something else.

Other programs that DPA members support include health education, HIV/AIDS, and environmental preservation. In the Northwest Territories, for example, the water is pristine, and mining companies have to demonstrate that the water they put back is more pure than the water they take out.

“It’s not about programs, it’s just how you have to operate. When you employ 77,000 people globally, and you buy 90% of what you need locally, you have a huge multiplier effect. We create about $16 billion of value, of which $14 billion goes directly to local communities through employment, taxes, et cetera. The real benefit is the share in the value creation, not just social programs.”

Bonke, the Middle East/India/Africa regional CEO for the Shangri La hotel group, said, “The principle we’re guided by is that we’re a business and must make a profit, but that profit allows us to fulfill our obligation we have as a business to reinvest in the communities where we do business.”

Shangri La tries to do as much business as possible in the local community and has developed specific programs to allow the company to be credibly local. For instance, it partnered with a home for people with speech and hearing impediments to learn to work in hospitality, and it now has 16 fulltime employees with such disabilities working at the company’s hotel in Delhi, India. Similarly, in Malaysia, the company has partnered with Cheshire Home for children with disabilities, and has trained them to work in landscaping, housekeeping, and other jobs around the hotel there. There’s even a takeaway food café run by employees from the Cheshire Home.

Two-thirds of Millennials and Gen-z say they will make shopping decisions based on sustainability, said Chris Rovzar. How can brands encourage that?

Get consumers involved, said Bonke. For instance, guests at the Shangri La hotel in the Maldives can go snorkel diving to plant coral. At another hotel, there’s a turtle hatchery on the nearby beach and guests can watch the hatchlings make their way to the ocean every year.

Lieberherr explained that the conflict diamond issue had a huge impact and left a lot of misconceptions lingering.

“2020 will be about bringing the diamond community to talk about how diamonds impact lives. Health, education, long-term employment, betterment in their lives. Not just mining, but also the cutters and polishers and everyone else.

“It’s good to hear not just from guys in suits, but all the people benefiting from it, from a woman driving a truck in Botswana or a guy working on environmental preservation in northern Canada.”

“We’re not making sustainability cool and sexy enough,” said Amandine Robin bluntly. The company’s Swedish Absolut brand vodka has been a leading example of making social issues cool. It was the first to embrace the LGBT community 40 years ago with a rainbow bottle made by the creator of the Pride flag, and everything about the brand is still made in a small village in Sweden and is carbon neutral. But it’s also how the message is conveyed. Not with charts and Powerpoint, but with authenticity.

“We say it’s the brand that gives a sh*t, not a brand that’s sustainable.”