Articles and News

Retail Innovator George Blankenship Of Gap, Apple, And Tesla, Addresses Centurion Jewelers | February 10, 2016 (0 comments)

Scottsdale, AZ—George Blankenship is the most famous name in retail that you never heard of.

How can someone be famous if few people know who they are? Simple. Consumers may not know who George Blankenship is, but chances are more than 90% of all Americans have been touched by him. If you’ve ever browsed or bought a product from one of the Gap brands or Apple—or his last venture, Tesla—he’s impacted your life, too. At the very least, if you’ve shopped at all in the last 30 years, the experience you had was likely to at least have been influenced by Blankenship’s theories, if not directly created by him.

Blankenship—who for six years spent up to four hours a day working directly with Apple wunderkind Steve Jobs—gave the keynote address for the Tuesday morning education session at the Centurion Scottsdale show, and in a meet-and-greet afterwards, attendees got to shake the hand that touched the hand, so to speak.

Blankenship began his career as a store manager trainee for Gap, at that time a retailer specializing in Levi’s jeans and an assorted hodgepodge of casual clothing. After 13 months, he got a bad review for spending too much time with customers and not enough cleaning the store—for which he promptly was promoted over the head of the reviewing manager. He spent a total of 20 years at Gap, first winnowing down the retailer’s jumbled assortment to a tightly edited private label grouping with a consistent point of view, and developing the concept of a store for each demographic: Banana Republic for affluent consumers, Gap for mainstream consumers, and Old Navy for value-driven consumers.

“Instead of 12 sweaters for men, we offered four. But they were the right cut, the right fit. Customers trusted us to be their editor. No matter where you went, you knew that you would never be embarrassed wearing something from our stores,” Blankenship told the audience.

George Blankenship transformed Gap from just another place to buy Levi's to a retailer with a distinctive point of view.

As “Gap-ification” became common practice in apparel sales, it inspired Steve Jobs, CEO of Apple. After all, he had to get dressed every morning too.

At the time, said Blankenship, the only thing most consumers knew about Apple computers is that they didn’t want one. Like the ill-fated Beta VCR format, Apple was expensive, it required special software, and it wasn’t compatible with anything else on the market. Luckily, Steve Jobs did one thing Sony’s executives didn’t: he made a call to Mickey Drexler, CEO of Gap, and asked to pick his brains about retail. Drexler brought Blankenship, the driver behind his successful stores, in on the call.

Like the earlier incarnation of Gap, computer sales of the time happened in big-box stores like CompUSA, which focused on volume, not experience. Instead of encouraging consumers to interact and try the products, most computer retailers discouraged even touching the products, let alone playing with them and using them in the store.

Jobs realized that if he could sell computers the way Banana Republic sold clothes—turning the process into a fun experience and introducing consistently good design to the product offerings—he would have a winning combination. He lured Blankenship away from Gap and the rest, as they say, is history.

Steve Jobs transformed the Macintosh to a design statement at a time when computers were strictly utilitarian, and the shopping experience was equally uninspiring. Below left, a CompUSA store; below right, an Apple store.

The first Apple store opened in 2001, with lines waiting around the block to get in and it sold out of inventory almost immediately. Business Week columnist Peter Burrows acknowledged Apple’s success, but remained skeptical of its long-term appeal. “They’ll be turning the lights out on an expensive and painful mistake in two years’ time,” he predicted.

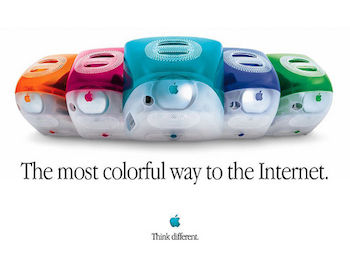

By then, Apple’s typical computer had been redesigned and rechristened into the candy-colored iMac (above), but something else happened that year that would change the course of not only Apple’s history but that of the entire audio category: the iPod was born.

“1,000 songs in your pocket,” Blankenship told the audience. But the first iPod was expensive: $600.

“Think like Mickey [Drexler],” he thought to himself. The iPod was already making history but it was out of reach for many. How to expand it across a wider range of income demographics? The iPod mini, introduced in 2004, was $247, and the Shuffle, introduced shortly after, was under $100. Now everyone could buy into Apple—just like Gap did with its Banana Republic and Old Navy divisions.

Top, the iPod Nano succeeded the Mini at a midlevel price point; bottom, the iPod shuffle was the entry-priced offering.

But Jobs had something else up his sleeve. “In 2007, Steve Jobs announced he was going to do a phone,” Blankenship told the audience. People who had never even used an Apple product lined up for blocks to get the first iPhones, and to this day, all smartphones still basically resemble and iPhone.

Why were people so anxious to own an iPhone? Very simple: it was the fun factor. One of the first apps ever created was a virtual beer mug (iBeer in the iTunes store.) As the user tilts the phone like a glass, the beer disappears, ending with a frat party belch. Blankenship demonstrated and the Centurion audience erupted laughing (and surreptitiously downloading) while he explained the simple reason why people wanted an iPhone: “my phone doesn’t do that.”

Three years later, Apple launched an entirely new category with the iPad—again, a groundbreaking device that all other tablets resemble to this day.

“Why do people buy Apple products? Because they want them!” said Blankenship. “People got pissed off when it wasn’t in stock and we couldn’t sell it to them on the spot!” But why did people want Apple products so badly, and why did they want to come to Apple stores?

“Innovation, design, simplicity, and experience,” he emphasized. “Design and deliver a great space, hire great people, train them very, very well, and turn them loose [on customers]!

He likened Apple’s retail experience to jewelry shopping and singled out two Centurion retailers, Diane Christensen and Colleen Rafferty of Christensen & Rafferty Fine Jewelry. Blankenship, who lives near the store, frequents it to buy gifts for his wife.

“People want things that make their spouses smile. They want something cool and different,” he said.

“What can you do to make people want to buy again and again and again? Make people feel important! Reassure them they’re going to be taken care of!” he drilled.

He again highlighted an anecdote involving Christensen & Rafferty: he was in a hurry and didn’t have time to go to the store, so Diane Christensen got it ready and met him in the parking lot of a nearby Walgreens to hand it off.

“We looked like drug dealers,” laughed Blankenship.

He also offered the Apple Genius Bar as an example of taking care of people. Originally designed a place to learn, it was so overwhelmed with customers that again Blankenship had to ‘think like Mickey.’ He broke down the Genius Bar into three more experiences: the Bar itself remained to handle technical issues with equipment. But to learn how to use the equipment, customers can pay $99 per year to take an unlimited amount of classes and/or one-on-one instruction in the store, focusing on a variety of topics. Those who don’t want to pay $99 can join one of many free workshops and learn in a group setting.

He also discussed how important it is to be nimble and adaptable. Not long ago, Napster made headlines as college students freely shared music. Record company CEO’s raced to sue the offenders, but Apple harnessed the power with the iTunes store and simply sold the songs for 99 cents. Problem solved, and by May 2014, the 35 billionth song had been downloaded from iTunes.

How did Apple become a retail legend? By being the best of class in music, mobile phones, computing, retail experience—and babysitting.

Yes, babysitting. Whereas a store like the late CompUSA might have sent a manager scurrying to pry a device out of a toddler’s sticky hands, Apple encourages play. And Mom and Dad just keep spending and spending.

The same principle helped Blankenship create a revolutionary new automobile-buying experience at Tesla.

After leaving Apple, Blankenship spent a brief period of time consulting for rival Microsoft, when he got an email from Elon Musk’s assistant. Musk was the creator of the Tesla electric car.

Blankenship thought the email was spam and deleted it. Musk emailed again. He deleted it again. Finally, he read it through, and went on to create a revolutionary new way to buy a car: at the mall.

Tesla is a story of the impossible, said Blankenship. Everything that Tesla is—a safe electric car that goes fast, recharges from a regular outlet, and is utterly luxurious—is something people said couldn’t be done. So was making the car-buying experience fun.

Blankenship applied the same babysitting principle to Tesla that he did at Apple. “Imagine putting a sticky kid into a Mercedes!” he laughed. But at Tesla, parents are encouraged to put their children into the car—even if the six-figure price tag makes them blanch—because, said Blankenship, who isn’t going to snap that picture and Instagram it or put it on Facebook?

Tesla is the first successful American car company since the 1950s, he said. And yes, “think like Mickey” is part of the plan: the current crop of pricey Teslas are going to be welcoming a (roughly) $30,000 sibling as early as March, he said. You have to do the impossible first, but the original plan of Elon Musk is to see everyone driving a clean electric car.

“Who will close their eyes and envision the possible opportunities of the next 10 years?” he asked. What will the fine jewelry buying experience look like in the future? Will it be out of the glass case?

It’s all about making the connection and how you make the customer feel. Who will make a move that changes the customer connection forever?

“Someone is going to do it. Is it going to be you?” he concluded.