Articles and News

Retail Versus Resale: A Tale Of Two Luxury Worlds | August 09, 2017 (0 comments)

Merrick, NY—While luxury retailers and brands struggle to find their footing amid a changing consumer landscape, the secondary luxury market is rocketing. In the fashion category, growth in high-end apparel and accessories consignment is outpacing the full-price sector by 20%, says a new report from Fung Global Retail & Technology, a retail think tank. Fung Global anticipates the entire resale industry will nearly double in five years, from $16 billion in 2016 to $33 billion in 2021. Along with eBay, long the driving force in the online secondary market, high-end consignment websites such as TheRealReal, TrueFacet, and ThredUp are proliferating, bringing the opportunity to buy and sell designer and luxury goods to far-flung locations.

Jewelry and watches are part of the trajectory. According to an article in Luxury Daily, online jewelry reseller TrueFacet has seen 18% growth in jewelry costing $25,000 or more, and a 34% increase in the general price of jewelry sold on the site.

“There’s less stigma to gently used or previously loved jewelry than in the past,” says Craig Miller, CEO of Palm Beach, FL-based Peter Fabrikant & Craig Miller. Miller, who has decades of experience on both the wholesale and retail sides of the industry, feels manufacturers partly brought it on themselves because of rising prices over the past decade that in his view weren’t warranted for certain items. “If you [the consumer] can get a better price on something that can be polished and look brand new, why not?”

Craig Miller, left, and Peter Fabrikant, right.

Why not, indeed? Especially among Millennials, who Luxury Daily says are among the largest consumers of secondhand apparel. Only women over age 65 buy more. But when it comes to luxury resale, Luxury Daily says Millennials are the primary drivers, because they’re brand-aware but with less money to spend than older consumers. And their younger siblings are following suit: TheRealReal’s biggest customer demographic is 35 to 55 and predominantly female, but Gen-Z is its fastest growing group, outpacing Millennials by 35%, and men’s watch sales are growing twice as fast as other categories.

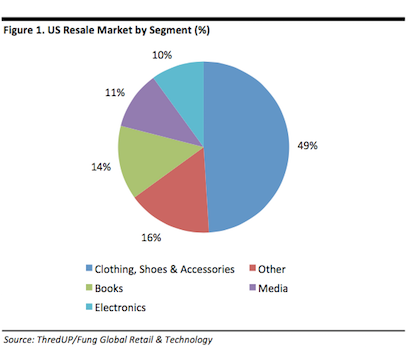

Total U.S. resale market by category. Source: Fung Global via Luxury Daily.

Experience-driven Millennials see resale shopping as a fun activity; i.e. the thrill of the hunt. And because luxury resale sites guarantee the authenticity of items sold there, there’s no reason not to feel confident.

“Our business model is based 100% on transparency and authentication,” says Michael Groffenberger, managing director of The RealReal’s luxury consignment offices. “Our [GIA] certified gemologists test all stones in order to ensure we are representing the product appropriately. We provide valuation reports with every single piece (including watches) and include any previous GIA certifications that were provided with the consignment. If a customer requests further information, he or she can speak with one of our gemologists to address any questions.”

Even on resale behemoth eBay, the buyer is much better protected than the seller today, says Miller.

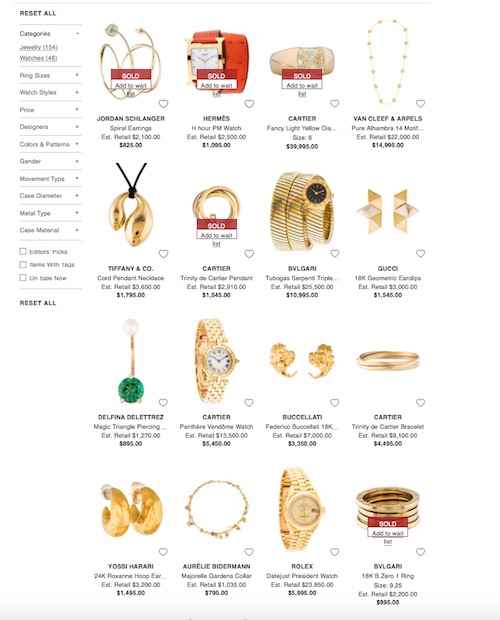

At multi-category sites like The RealReal, jewelry sales are rocketing. Groffenberger told The Centurion its fine jewelry and watch category is the fastest-growing on the site and the bulk of its secondhand jewelry retail is between $1,000 and $5,000.

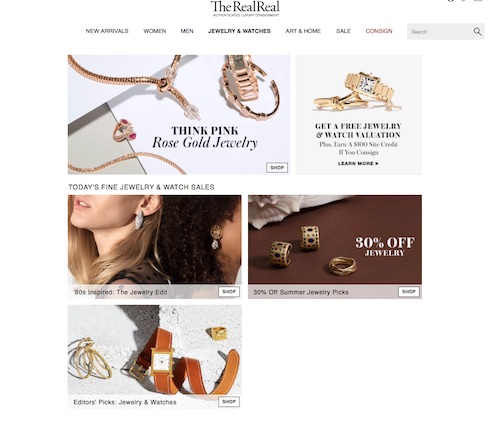

Jewelry and watches homepage on TheRealReal.com, above, and the Editor's Picks sale, below:

Offline, jewelry resale is even higher-end. Laura Stanley, formerly president of Stanley Jewelers Gemologists in North Little Rock, AR, and now a private jeweler, says $5,000 to $10,000 is routine for secondhand jewelry. She doesn’t sell a lot of watches now, but at Stanley Jewelers the sweet spot price for secondhand watches (other than Rolex President or diamond models) was between $4,000 and $7,500.

Laura Stanley at her microscope. Qualified appraisal is a key part of success in the secondhand jewelry market.

Jeffrey Singer, senior vice president and cofounder of CIRCA, has observed strong growth in two secondhand jewelry categories: midcentury modern jewelry and vintage steel sport watches from the same era.

Jeffrey Singer of CIRCA

“Like architecture and furniture (both in high demand now), midcentury modern jewelry comes from what I call the ‘cool and groovy’ era. If you remember the Sonny and Cher show, at the end of each show they’d come out and she’d be wearing the most gorgeous Pucci pantsuit, and these beautiful long gold chains with oval, circular, or square links.

“Within the confines of that timeframe, I would say jewelry by Cartier, especially Aldo Cipullo (top of page) mid ‘60s through early ‘70s, is most popular, although Van Cleef & Arpels of that era is a not-too-distant second place. Having said that, however, a lot of jewelry we buy isn’t signed. A lot of great jewelry sold in that period is not dripping with hallmarks or provenance. A lot of great manufacturers were the unsung heroes of that era.”

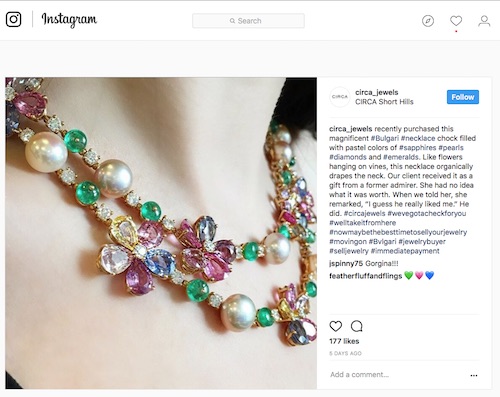

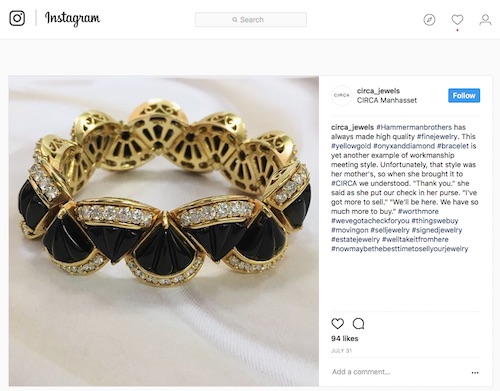

Two recent acquisitions at CIRCA include a Bvlgari necklace, top, and a Hammerman Brothers bracelet, bottom.

“I think there’s always going to be a market for the finer jewelry, the really well made, handcrafted, and period pieces,” concurs Miller.

A second category Singer says is still cresting—not even near its peak—is vintage stainless sport watches from the same era. Rolex leads the pack, of course, but Omega, Heuer (before Tag) and other brands made some racing, aviation, and non-chronograph sport watches with interesting cases. Although Singer calls the secondary market a “Rolex and Patek Philippe world,” (and Cartier, adds Stanley) he says these other pieces from the midcentury era are highly sought.

A gold Patek Philippe from Fabrikant and Miller.

“Maybe it’s nostalgia, but the trend is on a 25-degree incline going up with no sign of abating soon!” Prices for those pieces are often stratospheric, even hitting an occasional seven digits for a rare model.

Defining the market. What’s the difference between estate, vintage, and plain old pre-owned jewelry?

All of it technically is pre-owned, says Singer. “If it sold in a retail situation and gets sold back to resell, then it’s pre-owned.” Estate jewelry, meanwhile, used to literally mean it came from the estate of a person no longer living, says Singer, but the term has morphed into meaning pre-owned or antique. And, says Stanley, as an umbrella term, it sounds nicer than pre-owned or used.

Singer defines vintage jewelry as pieces from specific periods—Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Edwardian, et cetera—whose value is driven by design, provenance, and other factors that are not easy to replace and that far exceed the intrinsic value of the stones and metal.

Very little recent jewelry would be classified as vintage, he cautions. Some ‘70s and ‘80s jewelry might, if it was made by, say, Barry Kieselstein-Cord or David Webb or Bvlgari, but not necessarily if it was just derivative of the look or ordinary mass-manufactured fare.

David Webb earrings at Fabrikant and Miller, left, and Barry Kieselstein-Cord gold alligator earrings on auction site 1stDibs, right.

What becomes of big bold ‘80s and ‘90s Judith Ripka and SeidenGang pieces? Or even the David Yurman piece from five years ago that you just don’t wear anymore?

Both Miller and Singer say the biggest hurdle is for customers to get over what they think they should get for their jewelry.

“The good news is that if you’ve had these pieces three, five, or 10 years and your style has changed and your lifestyle has changed and you can divorce yourself from the price you paid for it or what someone told you you should get for it, you can say ‘this jewelry owes me nothing,’” says Singer. “A lot of fashion-forward women will buy a piece, wear it for a year or two, then she’s onto something else or wants a newer model from the same designer.”

Customers who wear jewelry as a fashion item like a handbag or shoes also need to realize that it might not even fetch as much as some handbags on the secondhand market.

“Generally, the retail secondhand market is around 50% of retail price, and the sweet spot starts at $300 to $500 and goes up from there,” says Miller. But a 50% discount is a strong incentive to buy designer jewelry from current brands such as David Yurman, John Hardy, and others, he says. Laura Stanley concurs, though she says discounts can vary from 40% less than new to more than 50% less for pearls. Both pearls and color are a consistently hard sell, she laments.

A pre-owned necklace and ring Laura Stanley recently sold.

One exception is Van Cleef & Arpels’ Alhambra collection. Don’t expect any bargains on this still-in-production line: secondhand pieces can fetch almost the same as new, or possibly even more for rare pieces.

Finally, what about just plain ordinary old jewelry? The omega chain and slide, the nugget ring, the gemstone brooch, or the three-row tennis bracelet that’s the jewelry equivalent of the big brown furniture Millennials don’t want?

“It seems to me that as some people are exiting the bejeweled lifestyle, others are entering it. There's never a shortage of people who want to show off, keep up with the Joneses, or just satisfy the desire they have always had for a diamond ring, earrings, or whatever,” says Stanley. “Also sometimes an estate piece can be reworked a little to make it desirable. For example, a brooch which we convert to a pendant. Or modifying earrings to be pierced, or sometimes making several items out of one big cluster ring.”

Miller says that while on one hand, there’s a customer for everything—even ugly jewelry—modern jewelry is more difficult to sell so people often decide to keep it and wait if they can’t get a certain value out of it. “But they don’t realize it’s a depreciating asset. As lifestyles get more and more casual, it gets less and less valuable.”

At that point, it’s going to be recycled the old-fashioned way: scrapped. And that’s when the quality of the piece matters most, explains Singer. “Take tennis bracelets. 500 companies from cheap to Cartier made them.” The better ones might sell intact, but even if they don’t, a platinum bracelet with G VS goods is obviously going to return more when broken apart than a cheap version. Circa still will try to offer the customer the most money possible for the piece, he says.

“I always tell clients that a piece is ‘worth its weight in gold and maybe more,’ depending upon the diamonds. Most people understand that. Lucky is the woman with a 10mm omega necklace she doesn't want anymore. They add up quickly on the scale!” says Stanley.

What the future holds. Despite resale being in hot growth mode, both Singer and Miller have a wary eye on future consumer shifts. Miller says the industry would be wise to understand the aspirational consumer and take a lesson from Mercedes-Benz, which when it saw its cars were being snapped up on the secondhand market, didn’t try and fight it but instead created the Certified Pre-Owned program.

Singer thinks the environmental and social responsibility appeal of secondhand jewelry could hold great weight with earth-conscious consumers, and the bargain prices can help turn aspirational customers into lifelong jewelry lovers. But the industry needs to move fast, he warns. “If we don’t grab this consumer in the next three to five years, there’s going to be a real problem. When they [Millennials] inherit jewelry, they’re going to sell it and use the money for something else they want: a vacation home, a trip to Bora Bora, or a Tesla. You don’t want this to become a gigantic global game of hot potato. There’s still time but not as much as there used to be.”