Articles and News

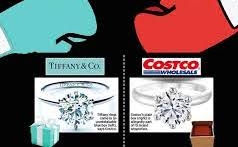

What The Tiffany-Costco Ruling Means For Luxury Jewelers | September 16, 2015 (0 comments)

New York, NY—Last week’s court decision in favor of Tiffany in its lawsuit against warehouse discounter Costco is not as clear-cut as it might seem. The discounter argued that the term “Tiffany setting” has become generic throughout the industry, and therefore it had rights to use Tiffany generally.

But that’s not what was at issue, says patent attorney Peter Berger of New York-based Levisohn Berger. Berger has been practicing intellectual property law in the jewelry industry for more than 30 years.

This case wasn’t about whether or not the term “Tiffany setting” is generic, says Berger. This was about the fact that Costco was using the word Tiffany without “setting,” or other modifiers to describe its rings—and that is not ok. Tiffany owns over 90 registered trademarks to Tiffany. Consumers interviewed by Tiffany for the case believed that the rings they got at the warehouse were genuine Tiffany & Co. jewelry, and were shocked and upset to learn that they were not.

Attorney Peter Berger

The judge did note that a registered mark can become a generic word, and that appeal courts have recognized a “dual use” doctrine in trademark law wherein a mark may begin as a proprietary word and gradually can become generic to some segments of the public.

“For example, the word ‘escalator’ began as a brand name but eventually it became a generic term for moving stairs,” explains Berger. “Today, the word can be a [protected] brand for clothing or any other category, but not for moving stairs.”

The term “Tiffany setting” has been used generically by the jewelry industry for many years, says Berger, and Tiffany didn’t fight it—potentially allowing a waiver of its rights to the term “Tiffany setting” for the prong setting commonly identified by the industry. Therefore, jewelers can probably still say “Tiffany setting” to describe a six-prong setting.

“I think the courts would probably allow that in a very narrow environment,” he told The Centurion. But jewelers can’t say “Tiffany ring,” or in any way imply that a ring is made by Tiffany when it is not.

“The term ‘Tiffany setting’ wasn’t before the court to decide because Costco was not accused of using that term,” says Berger.

Another recent case that actually has greater ramifications for luxury jewelers is the Apple/Samsung case. Apple sued Samsung for violation of the design patent it has on its trademark iPhone. The court decided in Apple’s favor and awarded damages of “total profits” for the Samsung phone. But the catch is how the court interpreted “total profits,” says Berger: the court’s interpretation was “gross sales,” making it an extremely expensive loss for Samsung.

A design patent lasts 14 years, he explained. It covers things beyond a copyright, and, in fact, companies do apply for a design patent if they can’t get a copyright because the design is too simple and geometric. A design patent is not limited to simple designs. A design patent is more complex to achieve, harder to enforce, costs much more and takes much more time than registering copyrights. But if a jewelry designer sues and wins a case under design patent law, then he or she can be entitled to the gross sales of the piece at issue—which does impact retailers selling infringing pieces.

Top image: blog.grayandsons.com