Articles and News

ERIC FREEDMAN: EXTREME SPORTS FOR AN EXTREME JEWELER | January 16, 2013 (0 comments)

Huntington, NY--You might think you know jeweler Eric Freedman of Freedman Jewelers. You might know he's a past American Gem Society president and recipient of its prestigious Shipley Award. You might even know that he has appraised the Hope Diamond. But you probably don't know he's a cave diver, an extreme sailor and a member of the prestigious Explorers Club (just like the astronauts, Sir Edmund Hillary, and Charles Lindbergh.) Oh, and his boat is named the Kimberlite. You know, the rock where diamonds can sometimes be found.

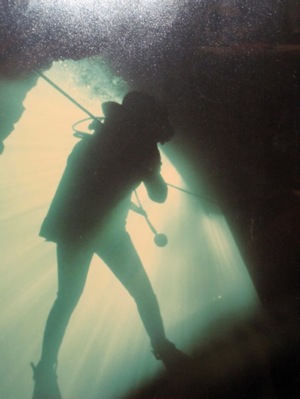

"I started diving when I was 12," says Freedman. "By 1976 I'd heard of cave diving, entering a water-filled cave with no air pockets. You have only the air you carry with you. It's one of the most dangerous sports in the world, one with many fatalities." Left, Freedman in his diving gear.

That did not deter Freedman. He trained in Florida and to become certified, he spent a week diving on and off at all hours. There were only three people in his class and he was the only one that passed.

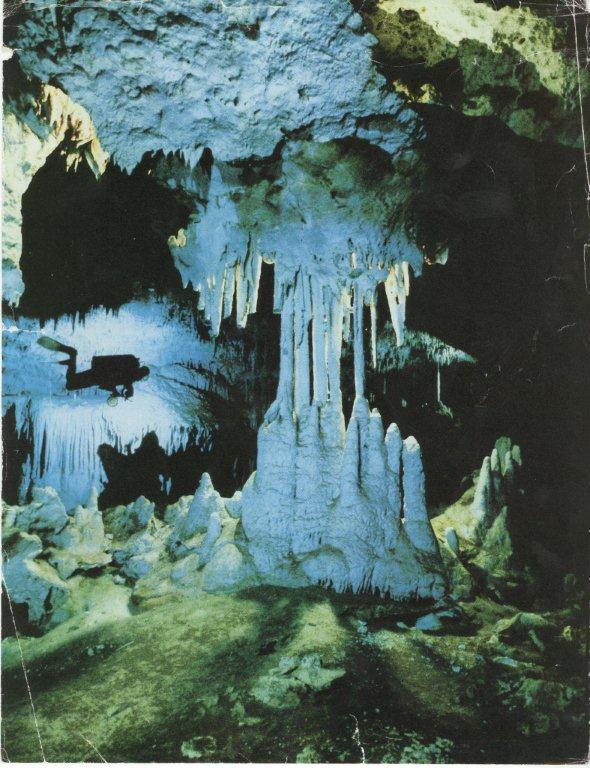

This is something even the most intrepid rockhounds might hesitate before entering: the inside of a water-filled cave.

To-date, Freedman has clocked 1,200 open water dives and another 1,000 cave dives. "You go places where no one on earth has been," said Freedman. "When I was diving, I couldn't buy equipment for this sport; it all had to be handmade." A cave diver goes as far as he/she can into the cave and lay a line that follows them into the cave (and shows them the way out). The diver goes until he/she cannot go any further for whatever reason, tie the reel off and leave. "A few months later, a diver that gets to that same spot or further will bring back your reel, and send it to you UPS. Then you can call up the friend that sent it to you and see how they are." Since the reels are handmade, the small group of cave divers all know what each other's reels look like, according to Freedman.

Freedman dove what is now his favorite cave in 1988. "There have been 45 deaths there," he says. "It's in Peacock Springs, FL." Freedman says that the water in cave diving is spring water. "It's like diving in bottled water. The visibility is incredible; you can see 1,000 feet or more on a good day." That is, until a diver kicks up silt at the bottom of a cave and can change the visibility to zero. "The silt has similar specific gravity to water," he says. So the silt takes time to settle; time that many divers do not have. The classes Freedman took taught him the proper techniques to propel himself forward and not disturb the silt. "Those without training can die."

Most jewelers would recognize Eric Freedman in a business suit, not a wetsuit.

Freedman dove for many years until he lost a buddy who died trying to set a world's record. "He was going to try to set a new record in a cave we called the Macho Pit," said Freedman. "It's very deep; I think it goes to Hell. The maximum safe depth for scuba is 120 feet. My friend, Sheck Exley, set the 700 foot record and was trying for 1,000 feet. He died doing it."

Freedman tapered off his diving after his friend died and after he got married. "Of the eight of us that used to dive together, three are alive today," he said.

While Freedman may not cave dive any longer, he does still sail a boat and doesn't let the weather stop him. He's sailed in a hurricane for 36 hours; sailed around the Mediterranean; around Europe; across the Atlantic; from New York to St. Martens by himself, nonstop. On that trip, he actually wanted to go on to Bermuda, but it would have taken more days and he didn't want to worry his wife, plus he knew she'd be mad when he got home. "It was fun," says Freedman.

Freedman has put 46,000 miles on his boat, the Kimberlite. At about seven miles an hour, that's a lot of time. This Kimberlite is his third. His first he sold to a guy in Detroit. The second one is in Switzerland on Lake Geneva. And he still sails the third, a 53 footer.

So, what does cave diving and boating have to do with jewelry? "Nothing," says Freedman. "I'm off work when I'm on the boat." And while he may be off work, he still meets people that want jewelry and want him to sell it to them. "People trust me; they like me, that's the secret of jewelry. I have many customers, some extremely wealthy, that shop with me from all over the country." Freedman met many through sailing, often parking next to a boat whose owners were famous.

But cave diving, sailing and jewelry do intersect, at least for a hands-on jeweler. "Being able to fix little things is helpful, since when diving or in the ocean there are no stores and no merchants," says Freedman. "If it breaks, you have to be able to replace it, repair it or jerry rig it. Being a jeweler helps me to do that when needed."

Freedman grew up on Long Island, near the water. "Sailing is the thing to do here," he said. He's certainly mastered that water sport and so much more.