Articles and News

EDITORIAL: LEARNING FROM STATUS BRANDS | August 17, 2011 (0 comments)

Merrick, NY—Status used to be simple. It meant having enough money to buy the best, and preferably a lot of it. Even significant historical figures who achieved greatness through character and achievement—think George Washington or Benjamin Franklin—usually also happened to be wealthy.

Status is the ultimate, but hidden, force that drives consumption. Subconscious, yet always there, it’s at the heart of every consumer trend, says an article on Trendwatching.com, a website devoted to tracking consumer behavior. Brands have the ultimate stake in helping people express themselves, impress their peers, and alleviate their anxieties about where they fall in the societal pecking order. But every status symbol is merely a tacit agreement among people to consider it such, and the article suggests that what constitutes status may be changing—and that no status symbol, even top brands, is invulnerable.

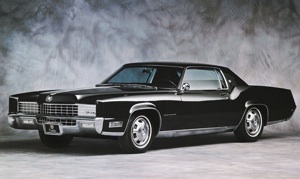

That’s true. Think back to the heyday of Detroit, when owning a Cadillac was the single most instantly identifiable means of announcing one’s success. The best of any category—whether it was a car or a snow shovel—was the “Cadillac” of its kind. It was inconceivable that the brand could be toppled.

But topple it did. Foreign auto brands were gradually making inroads into the American market, while Detroit rested on its laurels, ignored clear warning signs from consumers, and refused to acknowledge that tastes can change and a brand is only worth what a buyer thinks it’s worth. Suddenly a Mercedes or BMW became the new badge of success, and a Bentley, Aston Martin, or Maybach now offers an even higher level of automotive swagger. Meanwhile, Cadillac became the butt of jokes about elderly drivers hunched over the steering wheel.

The brand was in deep trouble, and GM seemed to have no clue how to rescue it. A number of early attempts to make it relevant again were abysmally misguided and, not surprisingly, flopped. Consumers didn’t relate to the brand as an “economical luxury” (Cimarron) or as a performance automobile that could compete with German imports (Catera). Moreover, the Cimarron in particular reeked of Detroit’s condescending attitude—it was essentially a Chevy Cavalier with a fancy grill slapped on the front. It wasn’t by any means a car that consumers wanted to pay top dollar to own, and instead of becoming a viable competitor to the snazzy small German luxury cars, it earned itself a place among Time magazine’s “50 Worst Cars of All Time.” The Catera didn’t fare much better—though built in Germany, its reliability record was dismal.

From this in Cadillac's heyday:

To this:

It wasn’t until fairly recently that Cadillac finally regained some measure as a status brand. The placement of its Escalade SUV in the HBO mob drama The Sopranos started to give it some much-needed street cred, and today the brand’s aggressive new styling is finding an audience among young men. It might not be the successful executive audience GM enjoyed in the past, but at least it’s been rescued from the brink of obscurity, a fate that befell several other GM brands.

Think about the brands in your store. Along with tracking your sales by SKU, do you track who is buying what? Can you look at any of your brands and quickly identify the typical customer for it? Have you seen any shifts in buying patterns for the brand over the past few years?

Do you observe that some of your brands that have widespread appeal across all demographics, while others seem to be drawing only one small segment of your customer base? That’s not necessarily a reason to drop the brand, but it is something to keep an eye on, realizing that at some point you may need to clear out that brand to make way for something else if its customer base drops off altogether.

In mature societies, the “statusphere” may be changing, according to the Trendwatching.com article. It suggests an increasing number of consumers are no longer solely obsessed with owning or experiencing the most and/or most expensive. Status for many—especially those still making their way in the world—still might mean the biggest and best, which is reassuring for established brands as long as they don’t make the same willful mistakes GM did with Cadillac. But for others it might be about eco-consciousness, new skills, connectivity, generosity, and other non-material forms of expression. Still, it’s not likely these customers are going to drop out of society and become ascetics tomorrow—but it does mean they’re going to be asking questions about a brand—and a store’s—contribution to society before they buy.