Articles and News

Jewelers Worry About The Wrong Things, Says Synthetic Diamond Panel | February 07, 2018 (0 comments)

Scottsdale, AZ—Synthetic diamonds, which many retailers believe pose their biggest threat, were the focus of the Monday morning education breakfast at Centurion Scottsdale. A panel of experts moderated by Centurion president Howard Hauben addressed the most pressing concerns retailers have around synthetic diamonds, mainly the increase in undisclosed stones being passed off as natural, and the resulting damage to a retailer’s reputation.

Panelists included Dr. James Shigley, distinguished research fellow at GIA (Gemological Institute of America), Christy Johnson, CCLA, personal lines claims examiner for Jewelers Mutual Insurance Co., and Nick DelRe, chief information officer for Gemological Sciences International, who also sponsored the session.

Dr. Shigley reassured retailers that identification of manmade diamonds is not only possible but also relatively easy.

“I know there’s great concern around synthetic diamonds, and we certainly have seen a lot that are very clear in color and clarity, but the good news is that synthetics have been studied for more than 30 years and a lot is known about identification and how they’re grown. Based on that research, we believe synthetic diamonds can be positively identified.”

The main identifier is short-growth vs. long-growth, explained Shigley. Differences occur in natural diamonds formed deep in the earth over billions of years, vs. those grown in a short time in a laboratory. Those differences are the primary identifiers of manmade stones.

“We do not believe that in the short growth of a lab you can reproduce the characteristic of long growth in the earth. You can replicate the properties, but not these long-growth characteristics. I won’t say never, but we believe it’s not likely to happen.”

DelRe concurred, adding that if it does happen it’s not likely to be in our lifetime. “They get the high pressure, the high temperature, but they cannot replicate the exact conditions of deep in the earth, so that part I wouldn’t worry about. But there are other things to worry about,” he cautioned.

From left: Howard Hauben, Centurion president, moderates a panel consisting of Nick DelRe from Gemological Science International, Dr. James Shigley, GIA, and Christy Johnson of Jewelers' Mutual Insurance Co.

Shigley said much of the panic arose from the fact that articles in the trade press tend to lump all synthetics into one category. But he sees synthetics in three separate categories—and only one of those gives real reason to worry.

The first category is very large, polished, five- to 10-carat stones, mainly coming out of Russia. “Every time we get one of these, the press makes a lot of hoopla, but they’re fairly easy to identify. Any large stone is going to go to a lab, so they’re going to be recognized. It’s not a problem,” he reassured the audience.

The second category is commercial sizes; i.e., two to two and a half carats. Shigley pointed out that most of the research on synthetic diamonds has been done in that category, which means it’s also not a big worry for retailers.

But the third category, melee size synthetic diamonds, is where Shigley sees potentially huge problems.

“This is the real ID challenge. Parcels can have mixes [of synthetic and natural] and not every piece of melee goes into a lab for identification or grading.”

At GIA, it’s very rare for synthetic diamonds to come in for grading report, he said. “They’re going somewhere, but not coming to us, probably because we identify them and put ‘synthetic’ on the grading report and manufacturers don’t like that.”

Christy Johnson, from Jewelers Mutual, next addressed some of the potential legal liabilities jewelers may encounter if a customer finds an undisclosed synthetic diamond in a piece of jewelry.

“The first thing to consider is your reputation,” she told the audience. “There’s a lot of money in the jewelry [you have], but that can be replaced. Your reputation can’t. You need to protect that.”

It matters what vendors you use, and what you are doing on the secondary market, she said. “A piece of estate jewelry may date from the 1920s, but you don’t know if a stone was switched,” she cautioned.

She also warned jewelers against making blanket statements. “You can say synthetics are ecofriendly but if one came from a supplier that uses fossil fuels, it’s same carbon footprint as an ethically run mine.”

If a jeweler is accused of selling a synthetic diamond as natural, how will they handle that?

Obviously retain professional courtesy, document all activity, attempt to de-escalate the situation and resolve it, but it’s better to avoid it in the first place by being very select in vendors and demanding accountability and disclosure, she said. Also, if you do sell synthetics, she recommends making a clear separation in the showcase so that they’re not mixed in with other merchandise, and have a return policy consistent with the store’s other merchandise.

Insurance will not necessarily cover you if you are accused, either.

“Commercial policies are not written for this kind of thing, so it’s likely not covered. It might be under an appraisal endorsement policy, but also very possibly not.”

For consumers with personal jewelry insurance, there is no coverage if they buy a piece of jewelry with an undisclosed synthetic diamond, but they would be covered if the piece were first sold with a natural stone that was later switched without the customer’s knowledge or consent.

Nick DelRe of GSI said pointedly that the jewelry industry is like a dog chasing its tail on this issue, and he approaches it from the opposite viewpoint.

“There’s been a lot of discussion over what to call manmade diamonds. Everyone focuses on this and spends too much time arguing, but what we really need to do is focus on rebranding natural diamonds.”

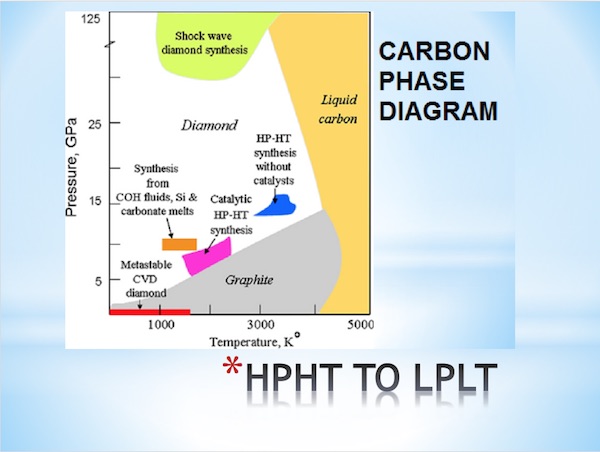

He showed a diagram (below) detailing what happens to carbon under different pressures and temperatures. “There are lots of recipes to make different kinds of diamonds. It’s fake for us, but wonderful for other industries such as electronics, optics, and so forth. Carbon is everywhere on earth, in all life forms.”

The problem, he said, is that once diamonds are cut, natural and synthetic stones look the same.

“Unless you have an experienced person looking at them, they don’t know what they’re looking at. Not all are textbook cases [of growth patterns and typical identifiers],” he said. “Disclosure is a step in the right direction, but not everyone discloses properly.”

He briefly addressed blockchain technology, which is being used in the financial field in Bitcoin. But even that isn’t a panacea, he cautioned. “On the surface it looks like a wonderful way to follow your product, but there still can be problems.”

He echoed Johnson’s recommendation of firm separation of the two kinds of stones in the store, which involves having the right procedures, instruments, and experienced personnel to maintain.

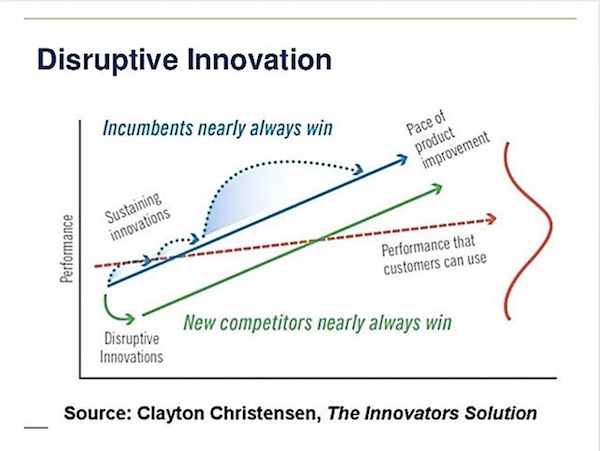

Disruptive innovation and technology always displace existing infrastructure and new companies will always find ways to undercut the bellies of established companies, he said, using the Internet and Amazon as examples.

“Ouch,” he said simply.

What’s driving synthetic diamonds’ growth—as with all disruptive technologies—is monetary gain and the idea of getting more for less. But disruptive technology should be framed as a marketing challenge, not technological one, he affirmed.

“It’s the technology part that initiates it, but marketing that makes it a success or failure,” he reiterated, reminding the audience that lots of money is being poured into synthetics.

“This is no joke. The industry really needs to counter this,” he warned.

Next week: The best tips for spotting synthetics, training staff, and addressing customer concerns.