Articles and News

What’s Ahead For Industry Financing, Lab-Grown Diamonds, And More | August 10, 2020 (0 comments)

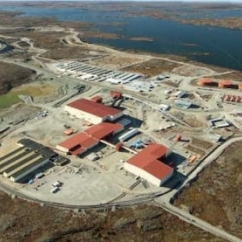

London, UK—In yesterday’s edition of The Centurion Newsletter, we examined some of the key issues the diamond industry is facing during the global coronavirus pandemic. In Part II of our series, four top diamond analysts offered these takeaways about industry financing, the future of lab-grown diamonds, and more, with CIBJO moderator Edward Johnson, GG, during the organization's Jewellery Voices webinar. Image: the defunct Snap Lake diamond mine; De Beers via CBC.ca

Edward Johnson: What has happened to diamond industry financing?

Pranay Narvekar, Pharos Beam Consulting: Financing to the midstream segment has been a challenge. But there’s been significant deleveraging of that sector in the last few years and it was a lot more sustainable now [and] going into this pandemic. Right now I don’t see financing as a top problem for this industry. If anything, interest rates around the world are at record lows and the world is awash in liquidity.

Edahn Golan, Edahn Golan Diamond Research & Data: 2019 was a very difficult year for the midstream diamond industry. To reduce expenses, many diamond companies reduced borrowing. They brought money from home and depended a lot more on their own money and that made them behave a lot more cautiously with their finances. If they had to trim fat, they did it.

It had two interesting outcomes: the supply of memo goods to retailers decreased, which put pressures on retailers to buy what they’re interested in or give up on it. In an odd plot twist, that created a lot of confidence on the part of banks, who saw the financing they provided standing on much more reliable legs. Bankers today will tell you if one sector is proving to be very reliable and meet its obligations in a timely manner, it’s the midstream.

But how long can diamond companies rely on their own money? At this point, they’re bringing money from home to keep the business alive, and the longer COVID and its effects linger, the more burden it puts on these companies. We might see some closures and defaults, but right now we’re seeing diamond industry as model.

Johnson: How can the industry restore trust among the finance community?

Russell Shor, Roshem Ventures: Pranay’s correct that there’s been a lot of deleveraging and it’s more sustainable now, but not for companies dependent on higher levels of credit. We’ve seen a lot go out and not seen a lot of banks coming in.

Frankly, we’ve had round-tripping, Fabrikant, Modi, and various other machinations. Banks also are facing trust issues themselves, like Deutschebank. There has to be a less [credit] dependent model. Alternative financing channels have been set up, but I’m not sure they can deliver kind of money needed to make a difference. And if you get one Modi-sized default, they’re gone.

The miners are traditionally cash-and-carry and maybe they have to be more flexible. Tailor sales to demand rather than what they want to get rid of so they don’t saddle people with goods they can’t move or don’t need and force them to borrow more to carry it.

Johnson: Are we any closer to becoming demand driven?

Paul Zimnisky, Paul Zimnisky Diamond Analytics: Yes, we’re seeing mines closing due to lack of profits. Mostly independents, though De Beers did close Snap Lake. This is not “keep producing and hope they sell,” this is “mines closed, ceased production.”

Related: How The COVID-19 Pandemic Revealed Structural Weaknesses in The Diamond And Jewelry Industry

Johnson: What’s going on with the lab-grown sector? Edahn, you produce data on lab grown purchasing and pricing.

Golan: We’re seeing a couple of very interesting trends. The first thing I do with a batch of data is separate bridal from everything else. One interesting finding is that business for bridal in terms of volume is steady, but retailers are not decreasing prices. And we thought we would not see lab-grown DER demand, but that’s increasing.

[Natural] diamond engagement rings on average are about $3200. Independents’ price of a lab-grown diamond engagement ring is about $3000. They’re keeping prices high and margins very good. At this point we’re not seeing very much willingness to compromise margins. (Editor’s note: Golan uses the overall average price of a diamond engagement ring; at high-end independent jewelers, the average price is significantly higher; $5,680 in 2018, according to The Knot.)

We’re also seeing an increase in stud earrings. Earrings have done very well from March through June. Earrings are a [typically] lower-cost item, and retailers are doing very good business with lower-cost items. And earring and even brooch growth is attributable to Zoom.

Shor: I’d like to put a bit of interpretation on Edahn’s statistic. What some retailers are saying is that consumers look at a $3000 natural diamond, and see they can get a more significant size for roughly similar money in lab grown. The retailers are saying the initial hesitation for lab-created diamond is fading. A lot more people are concerned about the future, the economy, and their job, but they don’t want a small engagement ring.

Years ago people would get a quarter-carat and upgrade once they became more affluent. One retailer told me now it’s lab-grown as the starter ring. You have this 1.5-carat lab-grown and maybe years down the line you buy a 1.5-carat natural stone to replace it. If you go to Blue Nile, what they’re pushing is clarity-enhanced [natural] and lab grown. The first thing you see is clarity-enhanced naturals, which are cheaper than lab grown for comparable sizes. As Edahn says, margins for lab-growns are much higher than naturals. (Editor's note: more than one attendee chimed in; Antoinette Matlins said lab-grown ruby, emerald, and sapphire created a new market for consumers who can't afford the quality they want yet but still dream of acquiring it. Another attendee, Alexander Klimchenko, said demand for lab-grown is currently outstripping supply, keeping margins up.)

Johnson: Let’s talk about sustainability. Is it an obligation or an opportunity?

Zimnisky: Apart from it being the right thing to do for humanity?

Golan: [Consumers say] for the price, I want an item that fits my morals. A lot of consumers will say ‘yes, yes, yes’ on sustainability but then they buy what’s cheapest.

Narvekar: [In India] from a purely business perspective it boils down to will there be extra value for them? Is there going to be more business or more margin? That’s when they will look at sustainability in a more proactive manner. If we can reduce the cost of compliance, we’ll see more participation.

Shor: The industry has a good story to tell but we don’t tell it well. We just cite Botswana or talk about how Gujarat used to be famine, but we don’t tell the story well. [If you show] video of a family who’s doing well and got out of poverty this shows how capitalism works without the greed stories you see elsewhere.

Johnson: Why does the industry need analysts and analytics?

Narvekar: The immediate answer is ‘we don’t need analysts.’ Everyone is their own analyst and thinks they can best predict what happens. That said, the larger companies do get it. You need to look at more than just the deal on the table and try to predict the direction the industry is going and take action in that way.

Golan: My father always said you’re good at what you’re good at, and you hire someone who’s good at what you’re not. That’s essential for your business. I think data and analytics contribute greatly to your business.

Shor: I think more analysts are needed, to be honest. It’s really critical to know what’s in demand and be able to tailor mine sales and mid-pipe production to that demand. Because otherwise you’re saddled with goods don’t need and debts you don’t want. It’s been an industry problem since I’ve been in the industry. Mining companies really need to figure out a strategy beyond selling run-of-mine.