Articles and News

The Year In Review, Part III: A Transformation Of The Diamond Industry And Volatility In Gold | December 30, 2020 (0 comments)

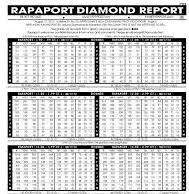

Merrick, NY—As we discussed in Part I and Part II of The Centurion’s Year In Review series, 2020 was transformational for the jewelry industry. For jewelers—and retailers in general—the pandemic lockdowns simply accelerated trends already occurring, such as digital selling. But for at least two industry institutions, 2020 was a tipping point for long-simmering resentments to boil over. The 103-year-old Baselworld Fair collapsed under the weight of its managers’ hubris and diamond trading would never be the same. In this installment, we examine what 2020 meant for diamonds and precious metals. Image: A Rapaport price list.

Diamonds. Going into 2020, lab-grown diamonds remained the big issue on jewelers’ minds, especially with the first national TV report of a couple who’d been scammed into thinking a lab-grown diamond engagement ring was natural.

Good Morning America ran an expose about a couple whose engagement ring turned out to be synthetic diamond.

The diamond sector was the first in the industry to grasp what the coronavirus might mean, when quarantines in China forced New Year festivities to be canceled in early February and diamond demand fell sharply. Experts began to worry about a return of oversupply of both rough and polished.

But the virus was about to change everything in the world of diamond trading. Martin Rapaport’s famed price list (top)—which dealers grumbled about but didn’t dare ignore—listed a steep drop in prices for March as the pandemic swept the world.

Dealers were furious. “Prices haven’t gone up, prices haven’t gone down, prices haven’t gone anywhere,” New York-based diamond dealer Ronnie VanderLinden told National Jeweler at the time. Trade was just nonexistent, he said.

Rapaport refused to change his prices but conceded that with essentially no trading going on, suspending the list for a month made sense. But it was too little, too late. The industry sensed an opportunity to do what it had long wanted to: ditch Rapaport.

Diamond companies both large and small pulled their goods off the RapNet trading platform. Rival IDEX made its trading platform free for all newcomers through August, and the World Federation of Diamond Bourses announced it would create a new platform for the entire industry. The Israel Diamond Institute also invited all WFDB members to use the IDI trading platform until the new one was up and running.

“He really stepped over the line,” said VanderLinden, who is president both of Diamex, one of the companies that pulled its goods off RapNet, and of the Diamond Manufacturers & Importers Association of America.

Meanwhile, the notoriously slow-to-change diamond industry got the new WFDB platform, named Get-Diamonds, up and running in less than six months and tapped industry veteran Kim Pelletier as its CEO.

Diamond industry veteran Kim Pelletier was tapped to lead the new Get-Diamonds platform, which was up and running less than six months after the industry collectively walked away from RapNet.

Diamond and jewelry sales, meanwhile, rebounded as the pandemic drove consumers to take stock of what’s most meaningful in their lives. Relationships were solidified with engagements and De Beers reminded the industry that old-fashioned emotion has gotten us through every other crisis and will again. But there are some structural weaknesses in the industry—financing and the supply cycle among them—that were already creating problems that the COVID pandemic simply accelerated. Those will need to be addressed.

The Diamond Producers Association, founded four years ago to rebuild generic diamond category advertising, changed CEOs and under the leadership of incoming CEO David Kellie was relaunched as the Natural Diamond Council. Kellie, whose background is in luxury fashion, took over in January from Jean-Marc Lieberherr, the founding CEO whose ties to the mining sector helped build the organization and get it ready for Kellie to take it to the next level.

In a letter to the industry, Kellie joked about being an outsider but so far it seems like his instincts are exactly what the industry needs. In that vein, the DPA’s original “Real Is Rare” message has evolved, as it needed to.

Former luxury fashion executive David Kellie is bringing much needed outside perspective to marketing diamonds.

The diamond sector also faces another major crossroads ahead with the closing of Australia’s famed Argyle mine. The mine produced breathtaking pinks and reds for the luxury industry, but the marriage of Australian near-gem diamonds and inexpensive Indian labor built the commercial sector that brought $999 (or even $99) tennis bracelets into the hands of consumers that otherwise never would own one. These may not be the primary customer for better jewelers, but someday they might be if their budget allows, so getting them interested in diamond jewelry is only going to benefit everyone.

The big question now is where those goods will come from next: another mine or a laboratory? The answer remains uncertain.

Argyle's famed pink, purple, and red diamonds will likely rocket in value now that the mine is closed, but the end of its commercial production of low-end stones leaves a void in the market that may ultimately be filled with synthetics.

Gold. As the coronavirus swept around the world, the gold market grew volatile. Initially, it didn’t seem to react too much, somewhat to industry surprise. While people generally assume that gold prices and the stock market have an inversely proportional relationship, that’s not really the case. Although gold initially jumped when the virus was declared a pandemic, prices quickly retreated to a three-month low. But then gold started climbing for real, and analysts began predicting it would hit $3,000, well above its previous all-time high of $1917 an ounce in 2011.

Then, as if $3,000 weren’t gulp-worthy enough, analysts soon started tossing out numbers like $4,000, $5,000, and even $10,000 an ounce. Ultimately, those numbers never materialized but gold did hit a new record price of $2,067 in August. But while it’s a record, it wasn’t anywhere near the earlier stratospheric predictions and, taking inflation into account, is still below $2200, which is what the 2011 record of $1917 would be in today’s dollars.

Renowned gold expert Przemsylaw Radomski, who looks for patterns in the gold market, believes 2013 will offer the best model for predicting gold pricing in the coming months. Meanwhile, the ultimate result is that “2020” was a harrowing year on many levels, but it’s not a price tag for gold—yet, anyway.

Platinum and silver. If there’s been a silver—or platinum—lining to the high price of gold, it’s that platinum jewelry is poised to benefit from the volatility. A study conducted in September shows rising consumer interest platinum jewelry, and the growing Platinum Born collection is geared specifically toward female self-purchase, an increasingly important customer demographic. The favorable price of the metal (at press time, trading at $1055 to gold’s $1882) also bolsters programs like PGI USA’s push for platinum crowns to set diamonds and gems.

The Platinum Born collection is designed for female self-purchase.

Lastly, silver jewelry demand dropped 23% globally—underpinned by a plunge in India—while prices for the metal grew volatile during the year, rising an average of 38% intra-year. At press time, silver was trading at about $26 an ounce, approximately a 30% rise year-on-year. U.S. silver jewelry demand also dipped modestly in 2020, but most of the volatility is coming from industrial demand fluctuations driven by the pandemic.